Yes, I get it: not your favorite topic. Taxes are neither thrilling nor simple, so naturally, like your mistake of an ex, most people want as little to do with them as possible. But as your favorite CPA, I’m going to make this easy for you. I’ll avoid all the technical jargon to give you the most important information in a way you can understand and remember.

Taxes have two characteristics that make the topic challenging to learn: tax rules are (1) overly complicated and (2) frequently changing. With this in mind, we’re going to focus on the basics. I’ll cover the information the vast majority of you will need to know to minimize your tax bill and accurately file your taxes, and I’ll highlight those areas that are ever-changing which you may need to reference for the applicable tax year. That’s as easy as this can get.

My recommendation is to read this post every year (we’re talking less than an hour, people), sometime between January and April 15th, before you start the tax-filing process. Read this once and you’ll feel confident in your general understanding of taxes. Read this every year before filing and you’ll feel confident in your ability to accurately file your taxes, regardless of the method you choose. Let’s get to it!

Note for 2020 filings: Even though 2020 might have been your worst year ever, there are some bright spots when it comes to your 2020 return to be filed by April 15, 2021. Between the CARES Act and other funding bills, many of these changes provide ways to put more money back in your pockets. Refer to the “COVID-19 Relief” section below for a list of these important tax changes that may apply to you.

Background

As much as we hate taxes, we can’t avoid them. From Pete Rose and Lindsey Vonn to Martha Stewart and Wesley Snipes, breaking tax laws can catch up to everyone. Even Chicago gangster Al Capone learned this the hard way. After all the nonsense Al Capone pulled—murder, bootlegging, corruption, weapons and so forth—it was tax evasion that did him in. He received an 11-year prison sentence, some of which he spent at Alcatraz. Don’t let this be you!

Infamous to us all, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) collects taxes for the U.S. government and administers the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), which is the tax rule book. This rule book, as you can imagine, is not a short read. Americans seem to always be pressing Congress to simplify the tax code as a means to prevent clever accountants and lawyers from taking advantage of tax loopholes to avoid taxes. In any event, the rules are the rules, and we must abide or face the risk of penalty.

With regard to the tax code, it’s important to distinguish tax evasion from tax avoidance. Whereas tax evasion is illegal and can put you behind bars, tax avoidance is perfectly legal and should be your goal. When you go to a movie theater to buy a $10 movie ticket, do you voluntarily offer to pay $20? Hell nah. Similarly, why pay the government more than what they require? It’s your responsibility (and should be your priority) to minimize your taxes using rules and methods approved by the IRS.

Tax Timing

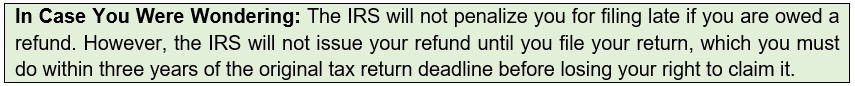

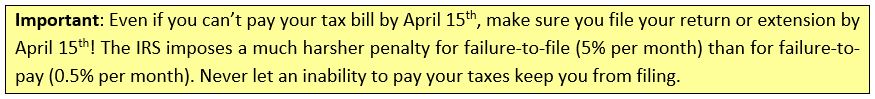

The first thing you need to know is your tax filing deadline: April 15th (or up to a few days afterwards depending on weekends/holidays). Believe it or not, many people forget this. Even responsible adults can say “Oh s**t” on April 20th. This doesn’t make the IRS happy: they’ll hit you with a penalty of 5% per month on the amount you owe up to a maximum penalty of 25%. On top of that, file more than 60 days late and you’re assessed a penalty of 100% of your unpaid taxes or a specific dollar amount (usually a couple hundred dollars), whichever is smaller. This can be one hefty penalty.

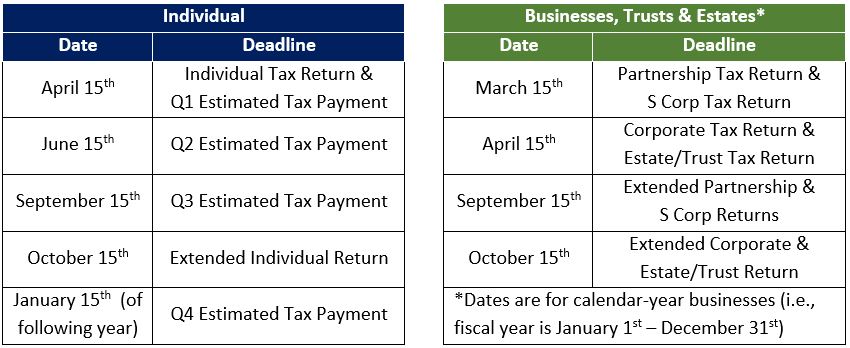

April 15th is the tax filing deadline for the individual tax return. But even though April 15th gets all the attention, there are many key tax dates that may apply to you:

Before you hyperventilate over all these dates, realize that ONLY April 15th will apply to the vast majority of you. The deadlines on the right are applicable only if you own a trust, estate, partnership or corporation. For the individual deadlines on the left, it’s important to understand the following:

Estimated tax payments: Who must pay estimated tax payments throughout the year? Those of you who expect to owe tax of $1,000 or more when you file your return. In other words, if you expect to receive a refund, you’re in the clear. If you expect to owe less than $1,000 when you file, you also made the cut. Since your employer is supposed to withhold taxes for you throughout the year, estimated tax payments are typically only required for those with investment or other income for which there are no tax withholdings throughout the year.

The obvious question here: how can you guess what you’ll owe Uncle Sam come filing time? The easiest way to predict this amount is to look at what you paid (or received as a refund) last year. The IRS will not penalize you if you pay estimated tax payments throughout the year totaling (1) 90% of your eventual tax owed in the current year or (2) 100% of your tax owed in the prior year (note wealthy taxpayers generally have a higher threshold of 110% of the prior year’s taxes, and there are exceptions for casualties, death, disability, etc.).

If estimated taxes apply to you, do not forget to use the criteria above to calculate the annual estimate, divide the amount by 4 and pay the quarterly estimates to the government by the quarterly due dates (note the first estimate for the following year is due on the same deadline for your current year tax return). Since calculating 90% of your predicted tax bill is a guess, make it easy on yourself by simply using the amount you owed last year. Fail to pay your required estimated tax and, of course, the IRS hits you with a penalty (more on this below).

Extended individual return: Upon seeing that the IRS has an option to extend your individual return filing deadline, you may jump for joy. Sit your a** back down. The key here: your tax payment is still owed on April 15th, regardless of whether you meet the original deadline or file for an extension. Otherwise, why would anyone in their right mind pre-pay the government on April 15th when they could wait until October 15th?

This option for an extension is really only for those who need more time to prepare their return. Although you don’t need to provide the IRS a reason, you still need to file a form (Form 4868) with your estimated taxes owed by April 15th to get the six-month extension. For those of you procrastinators gleaming at this option, do not file for an extension if you don’t have a real need. If you decide to file for an extension, you’re prolonging the pain of pulling off the band-aid while also putting yourself at risk of owing penalties on an underpayment of your estimated taxes owed at April 15th.

Even though individuals, corporations, partnerships and so on all have different tax rules, the focus for us will be the individual income tax filing: the one that will apply to all of you.

Federal, State & Local

When you file your taxes by April 15th each year, chances are you’ll have to file at least two returns: a federal return and a state return. You’ll file the federal return with the IRS, you’ll file the state return with your state’s Department of Revenue, and you’ll file a local return (if applicable) either as a component of your state return or to the local tax authority. Here are the requirements:

- Federal return: Most people are required by law to file a federal return. In general, you must file a federal return unless your earned income is less than the standard deduction (this amount changes each year and depends on your age and filing status). However, even if by law you aren’t required to file, you should strongly consider doing so as you could be throwing a lot of money away. Between income tax withholdings and an abundance of deductions and credits, you could have yourself a large refund owed to you by the government. As Wayne Gretzky said, you miss 100% of the refund you don’t take. Okay not quite his quote, but you get the point.

- State return: This one’s not as straightforward. Most of you will only need to file one state return, usually for your resident state. However, some of you may not even need to file a state return if you live and work in a state with no state income tax (at the time of this writing, these states include Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington and Wyoming). On the other hand, if you moved states during the year, worked in multiple states or even earned income from another state, you will generally have to file a state return for each of those states. Depending on your situation, this may require some research and/or inquiry of your employer.

- Local return: Local taxes, which are taxes levied by cities, counties or municipalities, are not as common. You should be able to determine whether local taxes are applicable to you by visiting your state’s Department of Revenue website or giving them a call. Oftentimes cities will provide you a notification in the mail if local tax is applicable, or your W-2 can also give you some insight as the form will show any local tax already withheld from your income.

Once you get the hang of the federal return, the state and local returns are very similar but with lower tax rates. Focus on the federal return for now, and we’ll briefly come back to State and Local at the end of this post.

Tax Bill or Refund

It’s one of the most mindboggling things you can see: people who celebrate getting a tax refund. This drives me nuts. It may come as a surprise that receiving a tax refund is not a good thing from a financial standpoint. Sure, I get that receiving money is always nice, but you can’t think like that in this scenario. A tax refund is really an interest-free loan you’re providing the government. Why do banks loan money? To earn interest. Why do investors loan money via bonds? To earn interest. Yet you’re happy to loan the government money without receiving interest? That makes no sense.

When you file your tax return by April 15th, you’re filing your return for the previous calendar year. For instance, your individual tax return for the calendar year 2020 is due April 15, 2021. Assuming you have any income during a particular calendar year, you know you’re going to owe tax on that money come April 15th of the following year. This is why your employer withholds part of your income each pay period: this money goes towards the tax bill you’ll have come April 15th of the next year.

Your goal should be to break even every April 15th, or at least have a relatively small tax bill. Have too high of a tax bill and you may owe the government interest or penalties. And, again, a tax refund is really a free loan to the government—money you could have invested elsewhere during that same time period (see the post on time value of money). This is why it’s important to pay attention during the calendar year: take a look at how much your employer is withholding, how much income you have that is not covered by a withholding and how much you are paying the government in estimates throughout the year (if applicable). Your guess of how much you’ll owe come April 15th certainly doesn’t have to be perfect, and it’s usually easier just to make adjustments after year 1 (the IRS also has a withholding calculator to assist you in this area). But please realize that a tax refund should represent a reason to decrease your withholding amount rather than a reason to celebrate.

Now take a deep breath, and let’s master the individual return.

Form 1040: Individual Income Tax Return

Introduction

If you’ve ever seen the U.S. Individual Income Tax Return (Form 1040), this thing is terrible. Other than being practical, it looks like something a dejected prison-worker put together at a funeral. The IRS could at least put a puppy or American flag in the background to make it a little more palatable. But Form 1040, including its six schedules, aligns with the tax formula and is the primary form you will need to understand.

What if you plan to use tax-preparation software? Tough noogies: you still need to know this. Understanding Form 1040 is key to understanding taxes. So pay attention, and enjoy the ride.

Filing Status

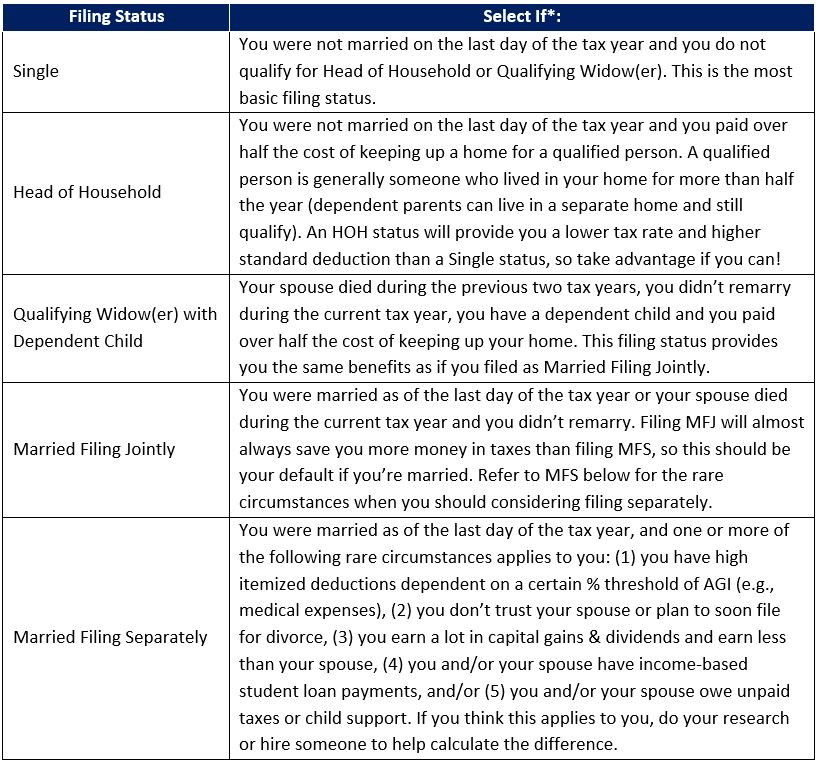

Your first step in filing your return is selecting your filing status. You have five options for your tax filing status, but you have even fewer options based on whether you were married or not as of December 31st of the year for which you are filing:

Unmarried: Single, Head of Household or Qualifying Widow/Widower

Married: Married Filing Jointly or Married Filing Separately

Selecting the wrong filing status is actually one of the most common mistakes taxpayers make (talk about stumbling out of the blocks). How do you know which is the right status for you? Here are the basic requirements:

*Each requirement has specific caveats for specific circumstances, so make sure you refer to the Form 1040 instructions to make sure you select the correct tax filing status. If more than one filing status applies to you, choose the one that allows you to pay the least in taxes.

Dependents

After selecting your filing status and documenting your personal information (i.e., name, address, social security number, etc.), you’ll then document your dependents. Why are dependents important? Because, contrary to sucking you dry financially on a normal basis, dependents can actually save you thousands of dollars on your taxes!

In particular, dependents come into play for tax credits and deductions, some of which are only available if you have qualified dependents. Believe it or not, dependents can make the difference between you owing tax and receiving a refund. So whom can you include as a dependent? Unfortunately not Fluffy the family cat. Here’s the definition:

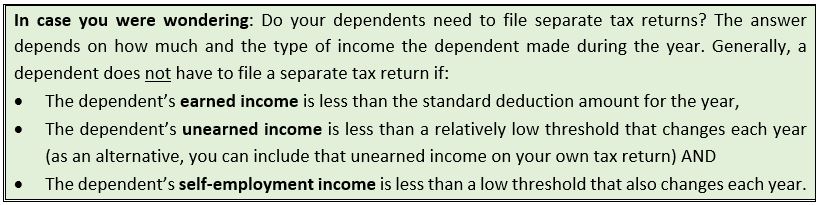

Dependent: To be a dependent, an individual must be a qualifying child or qualifying relative. The IRS provides detailed criteria for an individual to meet these definitions. In general, however, a qualifying child lives with you for more than half the year, is under 19 years old (or under 24 if a full-time student) and doesn’t provide more than half of his/her own financial support throughout the year. A qualifying relative is a relative (or non-relative who lived with you the entire year as a member of your household) for whom you paid more than half the individual’s financial support throughout the year. Refer to the Form 1040 instructions for the specific criteria.

After documenting your dependents, you also select whether each dependent qualifies for (i) the child tax credit or (ii) the credit for other dependents. We will discuss tax credits in more detail below, and you should reference the instructions in Form 1040 to determine whether your dependents qualify for these credits.

Tax Formula

We’ve covered a lot of background, selected our filing status and identified our dependent(s). Now we finally get into the nitty gritty and actually calculate our tax bill. To do this we’re going to walk through the tax formula (don’t go running for the hills—this isn’t that hard).

If we take a step back, the tax formula, at its most basic crux, takes our income and multiplies it by a tax rate to calculate our income tax owed. But the IRS allows us to reduce our income in certain circumstances, adds unique taxes for certain wealthy taxpayers and even taxes different income at different rates, which is how taxes get complex.

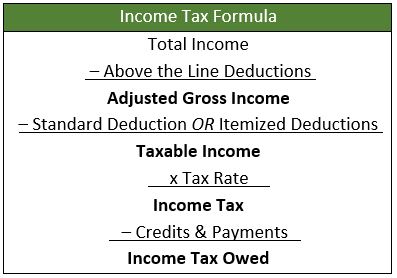

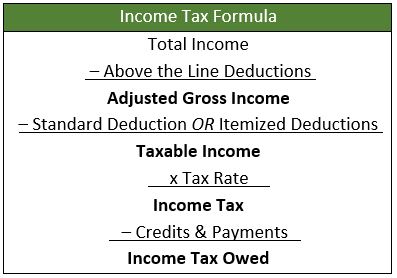

Regardless of how complicated taxes may seem, you should always come back to the following formula:

There are a lot of terms here you likely don’t understand: above the line deductions, standard deduction, itemized deductions, credits…oh my! Don’t worry: we’ll cover each of these in detail and then wrap it all in a bow. Ready? Let’s do this.

Total Income

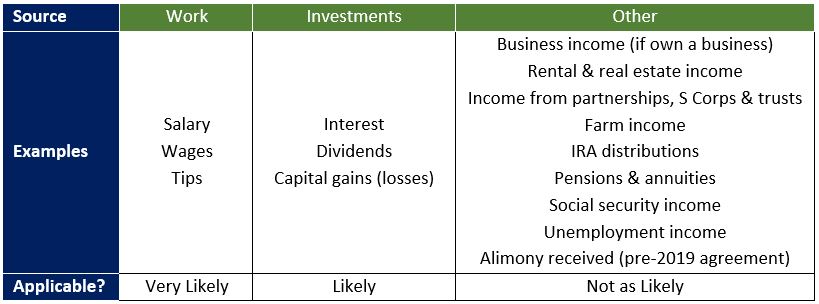

Your starting point for taxes is your income. This includes ALL of your earnings for the year, which typically fall into the following three buckets:

Each year when you file your taxes, you want to first think of all your sources of income:

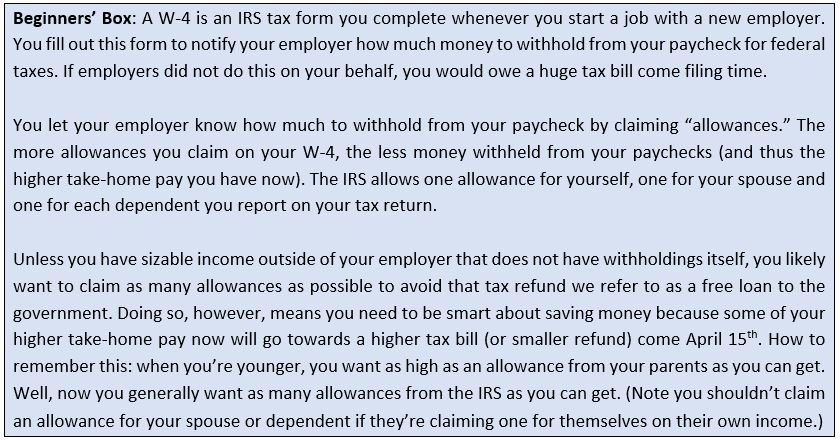

- How many jobs have you had? Consider one-off jobs, and think about how many W-4s you filled out for new jobs in the respective tax year.

- How many bank and brokerage accounts do you own? Do family members have any accounts held in your name? If so, income from these should be included (only if they’re not included on your family members’ tax returns).

- Do you personally own rental properties or real estate? Do you own your own business or have a stake in a partnership, S Corp or trust?

- Are you retired and thus likely to have social security income, pension income and/or IRA distributions?

- Have you earned any foreign income? Whether you’re a U.S. citizen or a resident alien, you must report that income to the IRS as well. If this applies to you, you’ll want to do some extra research to see how much, if any, of your foreign income you can exclude (the IRS sets an annual amount of your foreign earnings you can exclude from your U.S. income if you meet certain length and nature of foreign country stay requirements) and what foreign assets you will need to report. You may also qualify for a foreign tax credit, which we cover later in this post.

Each year, you should make a list of your income sources (e.g., employer, financial institution name, government entity). For each of your identified income sources, you need a form or other documentation supporting the income. Usually this support is delivered straight to your physical mailbox or email inbox, so be sure to save these forms when you receive them in January or February each year. If you don’t save the forms, you can usually request a copy of your W-2 from your employer and find investment forms stored on your online brokerage account. The following are the most common forms needed to report income:

Once you have identified your sources of income and organized all your supporting documentation, you’ve done the hard part!

If you use a tax preparation software (such as TurboTax or H&R Block), these programs make it extremely easy to upload the data from your income forms into your tax return. For example, to import the data from your W-2, the software will typically request you to fill in the control number (Box d), your employer’s Federal ID number (Box b) and your wages, tips & other compensation amount (Box 1). The software will then automatically upload your income and taxes withheld from the W-2. Easy peasy.

For your other forms, such as 1099-INT and 1099-DIV, the software will generally allow you to indirectly “login” to your financial institution’s account, which then automatically imports all tax-related forms on your account. For example, if you have a Vanguard account in which you have invested in several mutual funds, simply click on the Vanguard icon within the tax preparation software, login via the software, and voilà! The software will automatically import your Vanguard account tax forms and the associated amounts directly to your return. If your broker isn’t listed by the software, you will have the option to manually input the data from your tax forms to report your income. Just be sure to double-check your income amounts whether you input the data manually or automatically.

Above-the-Line Deductions (Exclusions)

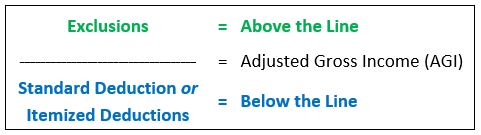

After you’ve reported your total income, the IRS allows you to reduce that amount by certain items to determine your “taxable income.” To do this, the IRS offers two separate categories of deductions:

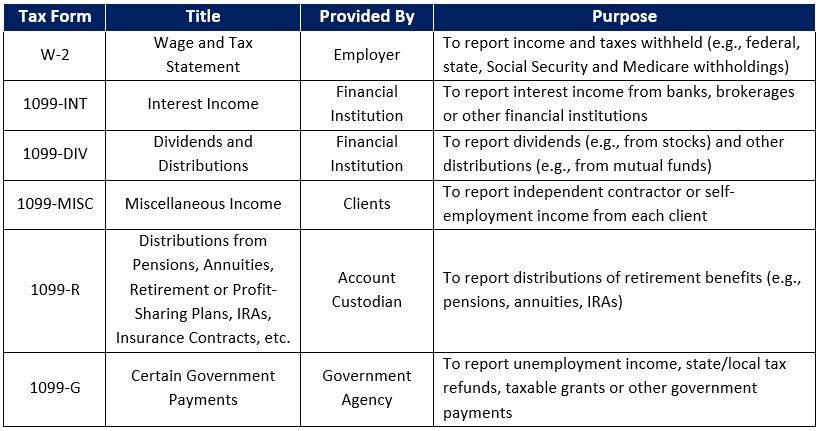

- Exclusions, which reduce your total income to your Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), and

- Either (i) a standard deduction or (ii) itemized deductions, which reduce your AGI to your taxable income

The term “exclusions” is pretty self-explanatory: there are certain classifications of income the IRS allows you to exclude from your taxable income. Don’t confuse these with the standard deduction or itemized deductions, although they generally have the same effect. The key distinguishing factor between exclusions and standard/itemized deductions is whether the deduction has an impact on AGI. In this regard, exclusions are often referred to as “above-the-line” deductions, and standard/itemized deductions are often referred to as “below-the-line” deductions:

Adjusted Gross Income is therefore “the line,” and above the line deductions impact AGI whereas the standard deduction and itemized deductions do not. Why does this matter? Because the IRS phases out certain tax benefits based on your AGI. For instance, as we’ll see later, there are certain categories of itemized deductions which must surpass a certain threshold of your AGI for them to be deductible (e.g., medical expenses); the IRS uses a modified version of AGI (i.e., modified AGI) to set the income threshold to determine whether you are eligible to contribute to a Roth IRA; and many states use your Federal AGI as the starting point for calculating your state taxable income. This is why above-the-line deductions are more beneficial than your standard or itemized deductions (below-the-line deductions).

What does the IRS allow as above-the-line deductions? The list below summarizes some of the key categories you can exclude from your AGI:

*These deductions can have specific limitations and caveats impacting eligibility. Refer to the Form 1040 Schedule 1 instructions for specific deduction amounts and eligibility criteria.

*These deductions can have specific limitations and caveats impacting eligibility. Refer to the Form 1040 Schedule 1 instructions for specific deduction amounts and eligibility criteria.

Don’t bother memorizing all these deductions and their associated rules. Rather, use this as a reference to ensure you include all of these deductions on your return (if eligible) and as a means to reduce your AGI if it will enable further deductions (e.g., increasing your IRA contribution to lower your AGI and further deduct medical expenses).

Adjusted Gross Income

Adjusted gross income (AGI) is also known as “the line” when considering deductions. As noted earlier, the IRS uses AGI as the basis behind many tax rules, including several tax benefit phase-outs and itemized deduction thresholds. Remember: total income less “above-the-line” deductions equals AGI. Easy enough. Now let’s move on to the “below-the-line” deductions.

Deductions (Below-the Line)

THIS IS IMPORTANT. Highlight this; underline this; get a tattoo of this:

Not everything that is “tax deductible” is in fact deductible.

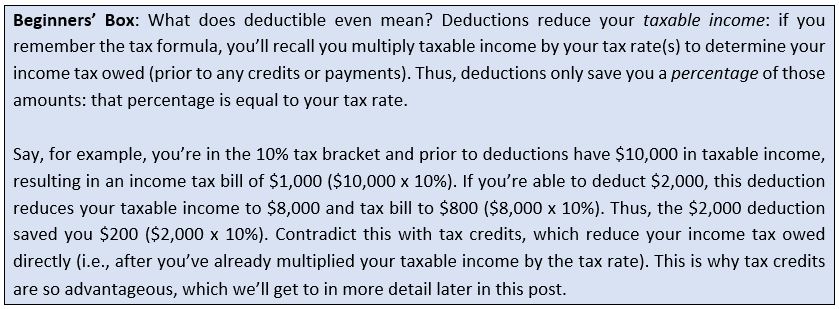

This is another area of taxes people often miscomprehend. Assume a relative of yours if fundraising for a worthy cause and reaches out to see if you’re willing to donate. She provides a pamphlet describing the cause and a donation’s impact, including a description that your donation will be 100% tax deductible. Oh, great! That means if I donate $100, it really only costs me $76 (assuming a 24% tax bracket) as I’ll deduct the $100 from my taxable income. Not necessarily.

Once you get past AGI, you reach a fork in the road at which point you must choose between two options for your “below-the-line” deductions:

Option 1: Standard deduction

Option 2: Itemized deductions

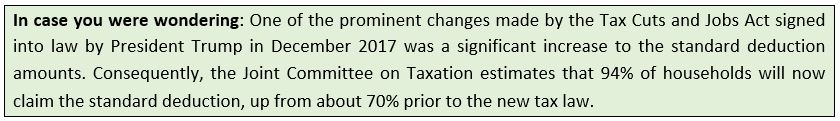

You can select either Option 1 or Option 2, depending on which provides you the greater amount of deductions. This requires you to sum up your itemized deductions and then compare those deductions against the standard deduction. Whichever is higher, that’s the road you’ll take. For the vast majority of you, the standard deduction will be the better option.

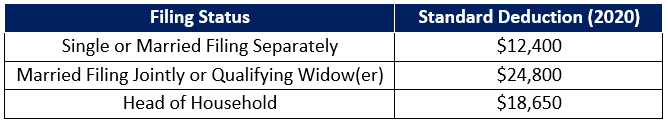

Standard Deduction

A standard deduction is relatively simple. It’s an amount set by the IRS each year for each separate filing status. For example, the standard deductions for the 2020 tax year are as follows:

Because the IRS makes everything complicated, there are of course some exceptions to the amounts above and restrictions on eligibility, as follows:

- Additional standard deduction: You can receive an additional standard deduction amount if you are blind and/or age 65 or older (for 2020, this bonus is $1,650 if unmarried and $1,300 if married)

- Reduced standard deduction: If you can be claimed as a dependent on someone else’s tax return, your standard deduction may be limited based on your earned income for the year

- Don’t qualify: You do not qualify to take a standard deduction in the following scenarios:

- You elect to itemize your deductions

- You file married filing separately and your spouse itemizes his/her deductions

- You were a nonresident alien or dual status alien during any part of the year

- You changed your annual accounting period and file for a period < 12 months

If you elect to take the standard deduction, you cannot deduct any other “below-the-line” deductions (which we cover in the itemized deductions section, below). This is one of the main reasons expenses which are “tax deductible” are not necessarily deductible for you. For our donation example above, your $100 donation would not be tax deductible if you take the standard deduction. Remember this whenever the standard deduction is the right choice for you.

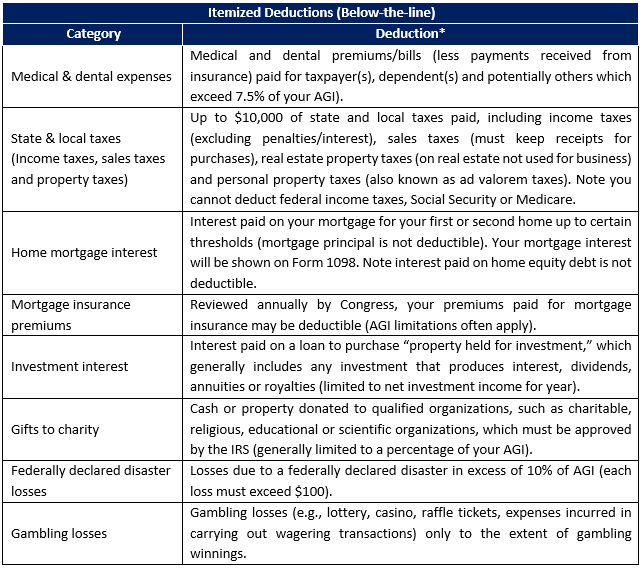

Itemized Deductions

If you don’t take the standard deduction, your other option is to itemize. With the new tax rules in place, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that fewer than 10% of households will itemize; however, those with higher incomes are much more likely to take this route. Whether you think you should itemize or not, you should calculate your itemized deduction amount each year to compare it to your standard deduction. This could save you some serious bucks!

Similar to above-the-line deductions, there are many categories of possible deductions to itemize. Most itemized deductions are based on a minimum “floor” amount: that is, you can only itemize certain deductions which exceed the specified floor amount. Examples of below-the-line deductions you can itemize are as follows:

*These deductions can have specific limitations and caveats impacting eligibility. Refer to the Form 1040 Schedule 1 instructions for specific deduction amounts and eligibility criteria.

*These deductions can have specific limitations and caveats impacting eligibility. Refer to the Form 1040 Schedule 1 instructions for specific deduction amounts and eligibility criteria.

Clearly there are a lot of options to include within your itemized deductions, even if most of the deductions have certain thresholds you need to hurdle. Every year you file your taxes, it’s worth referencing this list (and any changes made by the IRS) to ensure you have considered all possible itemized deductions to compare to your standard deduction.

If you elect to itemize, it’s very important that you retain supporting documentation for these deductions. This includes keeping detailed records for your charitable donations, medical expenses, state & local taxes paid, interest expenses or whichever other deductions may be applicable. Perhaps you should invest in a filing cabinet.

Deductions are one of the trickiest areas in taxes, so pat yourself on the back for putting this in the rear view.

Taxable Income

As Bon Jovi likes to say, we’re half way there! You meandered through the income moguls and even survived the double black diamond of deductions, so now all that’s keeping you from the hot tub is a nice glide down the bunny slope without running into any snowplowing kiddos. To celebrate, let’s put up that tax formula one more time:

Remember this formula? Please just humor me and say “yes.” By subtracting above-the-line deductions and either the standard deduction or itemized deductions from your total income, you’ve now arrived at your taxable income. Hopefully this definition is pretty obvious: taxable income is your income amount that is actually subject to income tax.

To calculate your income tax, you simply multiply your taxable income by your tax rate, right? HAHA! Yeah, right. That makes too much sense. By now you should realize the IRS is the worst and makes nothing easy. Okay they’re not so bad, but still.

Tax Rates

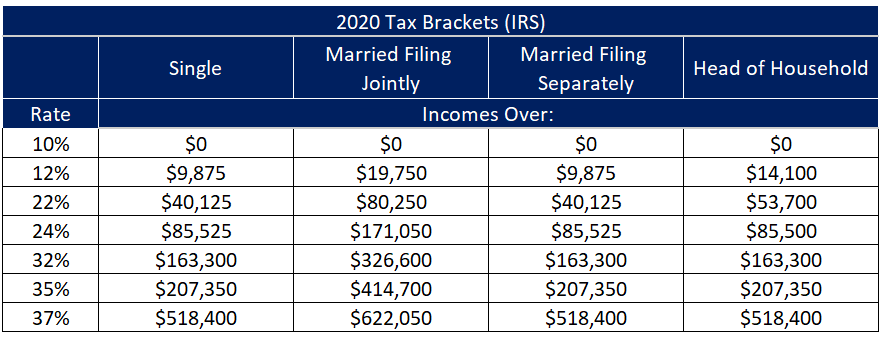

To the surprise of most people, no, you can’t just multiply your taxable income by your tax rate to calculate your tax bill (unless you’re in the lowest tax bracket). Rather, the IRS establishes progressive tax brackets based on income tiers, meaning different portions of your income are taxed at different rates. To illustrate, here are the federal income tax brackets for 2020:

As you can see in the chart above, at the time of this writing, the U.S. has seven tax brackets ranging from 10% to 37%. If you file as Single, you’ll notice that your first $9,875 of income is taxed at 10%, next $30,250 (40,125 – 9,875) is taxed at 12% and so on. This is why there’s a difference between your marginal tax rate and your effective tax rate:

Marginal tax rate: The tax rate applied to your next dollar of income (i.e., your current bracket).

Effective tax rate: Your average tax rate on all your income, considering you have tiers of income taxed at different rates.

Let’s consider an example:

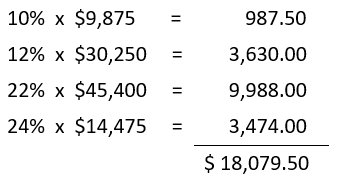

You have taxable income of $100,000 in 2020 and file as a single taxpayer (refer to the tax bracket shown above). Your income tax is calculated as follows:

In this example, your marginal tax rate is 24%: this is your “current” tax bracket, meaning any additional dollars of income you made in 2020 would have been taxed at 24% (until you made enough to reach the 32% tax bracket). Your effective tax rate is 18.08%: this is your average tax rate for your total $100,000 taxable income. Since your first tiers of income are taxed at lower rates, your effective tax rate will always be less than your marginal tax rate (or will be equal if in the lowest bracket).

If you use tax preparation software or hire a professional to prepare your taxes, you won’t need to calculate your tax bill yourself; however, it’s worth understanding both your marginal tax rate (i.e., current tax bracket) and your effective tax rate (i.e., average rate) to know the impact taxes have in your life.

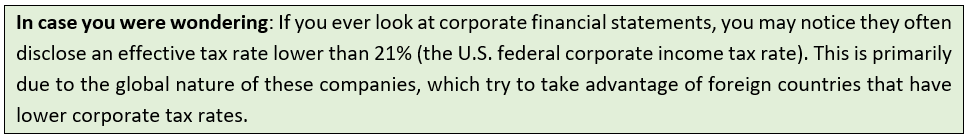

Qualified Dividends & Long-Term Capital Gains

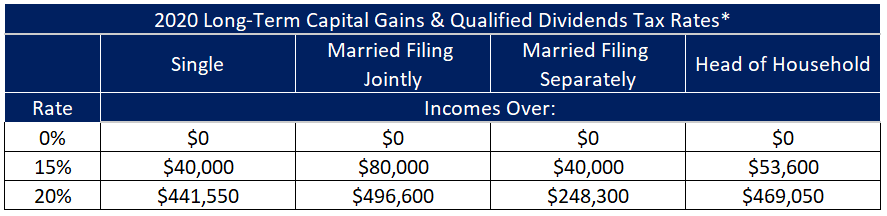

This is really important (not that everything else in this post is not), so follow closely. You may recall, begrudgingly, the IRS provides preferential tax rates for certain types of income. To incentivize you to buy and hold investments, the IRS provides a tax break on qualified dividend and long-term capital gain income. Rather than the “ordinary” income tax brackets discussed above, the IRS sets the following, lower rates for qualified dividends and long-term capital gains based on your taxable income:

*As part of the Affordable Care Act, high-income taxpayers must pay an additional 3.8% tax on net investment income, bringing the highest capital gains tax rate to 23.8%.

*As part of the Affordable Care Act, high-income taxpayers must pay an additional 3.8% tax on net investment income, bringing the highest capital gains tax rate to 23.8%.

Clearly the preferential tax treatment for this income can save you a lot of money: for most people, this could amount to a difference of 10-15%! What qualifies? Here are the basics:

Qualified Dividends: When you receive a dividend, it’s categorized as either qualified or ordinary. The IRS prescribes several rules for dividends to be qualified, but in general qualified dividends must be (i) paid by a domestic corporation or qualified foreign corporation and (ii) distributed from an investment you owned for at least 60 days during the holding period, defined as the 121-day period that starts 60 days before the dividend and ends 60 days after the dividend. You can see your amount of qualified dividends on Form 1099-DIV.

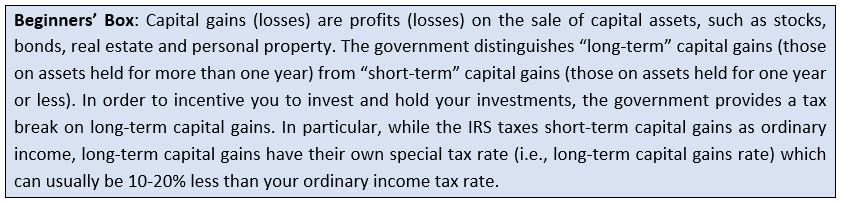

Long-Term Capital Gains: Capital gains are profits on the sale of capital assets, such as stocks, bonds, real estate and personal property. There are two types of capital gains: short-term capital gains and long-term capital gains. The difference is based on how long you held the investments before you sold them at a gain: if you held the asset for at least a year, the profit on the sale of the asset qualifies as a long-term capital gain.

As you can see, you can’t receive this preferential tax treatment unless you hold the associated investment for a certain period of time, explaining why short-term investing is not favorable in the world of taxes. Knowing this, make sure you tailor your investment strategy to take advantage of the tax rules. We’ll discuss what you need to know about investing in another post.

Other Taxes

Once you calculate your tax on original income and qualified dividends/ long-term capital gains, the IRS throws you yet another curveball. If you feel like you struck out a while ago, you’re not alone.

The IRS includes a section of “Other Taxes” on Schedule 4 of Form 1040 related to certain rare taxes requiring specific calculations. Oftentimes these taxes relate to amounts you may still owe on self-reported earnings, early withdrawals or credit repayments. In particular, Other Taxes include:

- Self-employment tax: Social Security and Medicare owed (as must pay both employee and employer’s share)

- Uncollected Social Security and Medicare tax: Any uncollected Social Security or Medicare tax on wages or unreported tips

- Early withdrawals from retirement plans: Owed on early withdrawals from IRAs and other qualified retirement plans

- Household employment tax: Owed if employ someone in your home (aka “nanny tax”)

- First-time homebuyer credit repayment: If you bought your home and qualified for the credit in 2008

- Healthcare individual responsibility penalty: If not covered by health insurance required by Affordable Care Act

- Additional Medicare tax: Levied on some high-income taxpayers

- Net investment income tax: Also levied on some high-income taxpayers

If any of these apply to you, make sure you fill out the respective IRS schedule or form. And try not to curse too much while doing so.

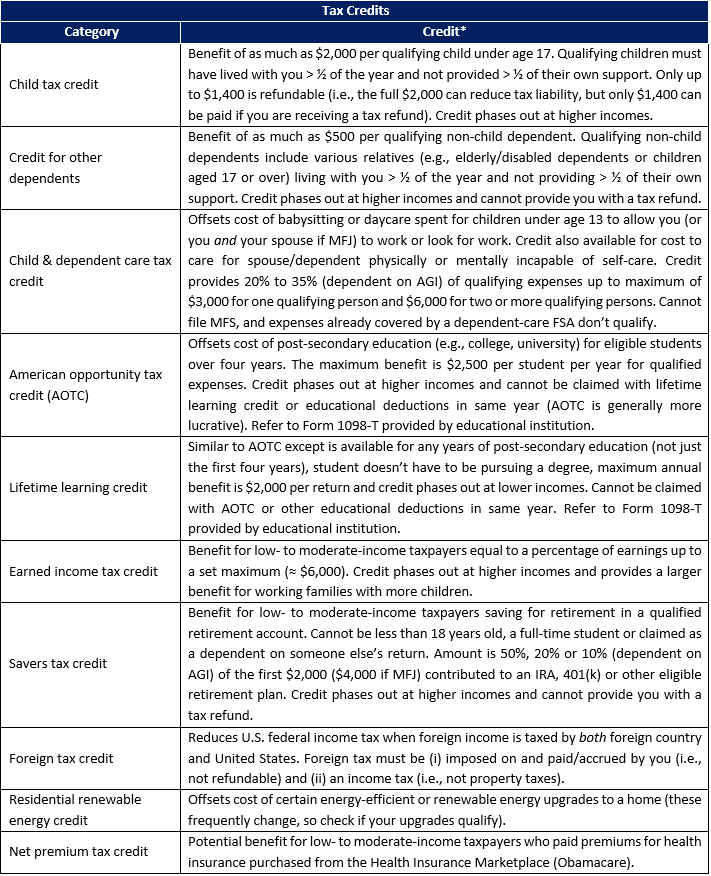

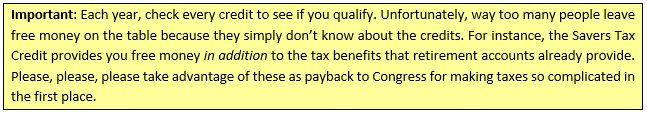

Credits

You’ve calculated your taxable income and multiplied it by the applicable tax rate(s) to determine your income tax. I’m sorry to say, but we’re not quite done yet. Try to contain your excitement. What about the tax payments you’ve already made throughout the year (e.g., withholdings and estimates), and how about that free money the IRS gives you in tax credits? If you’re bummed since we’re not quite done yet, be thankful since credits and payments can only reduce your income tax owed.

As mentioned earlier, tax credits are important to distinguish from tax deductions. It’s like ordering your favorite pizza only to have it delivered ⅔ eaten by your delivery guy. I would cry. Except in this case, the pizza stealing culprit is the IRS. Deductions, which end up getting multiplied by your tax rate, only save you 10% to 37% of the deduction amount. Credits, on the other hand, are direct reductions to your tax bill: providing 1-for-1 savings as if the IRS is handing you straight cash.

How do you get these uneaten pizzas? Here are the most common tax credits you can claim (not in order of Form 1040):

*These credits can have specific limitations and caveats impacting eligibility. Refer to the Form 1040 Schedule 3 and Schedule 5 instructions for specific credit amounts and eligibility criteria.

*These credits can have specific limitations and caveats impacting eligibility. Refer to the Form 1040 Schedule 3 and Schedule 5 instructions for specific credit amounts and eligibility criteria.

Payments

DO NOT forget about this step. Your W-2s usually have you covered from a tax withholding standpoint, but you won’t believe how easy it is to forget to include your tax estimates paid throughout the year (if applicable). Whether you use tax preparation software, hire a tax professional or manually file the return on your own, double check that your tax withholdings and tax estimates paid are included on your Form 1040.

Income Tax Owed

You’ve done it!! Subtract your tax credits and payments from your total income tax and you now have your final income tax bill or refund. Whew, take me to a bar immediately.

COVID-19 Relief

2020 was supposed to be a quiet year for tax change, and then WHAM! This dumb a** virus won’t leave us alone. Between the economic stimulus packages enacted in March 2020 and government funding bills, here are the key changes to know for your 2020 tax return:

- Recovery rebate credits: Remember that $1,200 stimulus check you received ($2,400 if filing jointly)? That stimulus check, if you were lucky enough to receive one, was technically a prepayment of a 2020 tax credit known as the recovery rebate credit. When you file your 2020 return, you’re required to reconcile the amount you received against the amount you were entitled to claim. For most people, the two numbers will equal, and the recovery rebate credit will be zero (i.e., no change to the stimulus you received). However, if your stimulus check was less than your credit amount, your tax owed will be reduced by the difference (and can even result in a refund!).

- Charitable gift donations: The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided a unique tax benefit for 2020. In particular, if you claim the standard deduction on your 2020 tax return—which, chances are you will—you can claim a brand-new deduction of up to $300 for cash donations made to a charity in 2020. Importantly, the deduction only applies to cash donations made to qualified 501(c)(3) organizations, and the deduction is capped at $300. If you made a cash donation in 2020, be sure to hold on to the receipt so that you have proof when it comes time to file your tax return in 2021.

- Self-employed tax credits: If you’re self-employed, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act offers you a credit against the self-employment tax if you can’t work because of the coronavirus (i.e., you would be entitled to coronavirus-related sick or family leave if you were an employee).

- Student loan payments by employers: The CARES Act also allowed employers to pay down up to $5,250 in employees’ college loans in 2020. If your employer paid assisted with your student loan debt under this provision, the payments are excluded from your federal taxable income.

Alternative Minimum Tax

If you were following along with the actual Form 1040, you may have noticed we skipped the line on Schedule 2 titled “Alternative Minimum Tax.” The main reason we did so is because this tax, which can be a nightmare for some, only applies under rare circumstances. Nevertheless, here’s a quick rundown:

The individual Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) is a separate tax meant to prevent wealthy taxpayers from relying on deductions to avoid paying their fair share in taxes. Specifically, higher-income taxpayers essentially must calculate their taxes twice—once using the standard system described above and once using the AMT calculation—and pay the higher amount.

In particular, higher-income taxpayers must add certain “preference items” to their taxable income, subtract an established AMT exemption amount (dependent on filing status) and recalculate their tax liability using specific AMT tax brackets. AMT represents the amount, if any, of this recalculated tax over the regular income tax. In case you’re curious, those “preference items” include standard deductions and certain itemized deductions.

The AMT only impacts 1-2% of the U.S. population, so chances are AMT will not apply to you. In particular, AMT most commonly affects wealthy taxpayers (but not the very wealthiest, oddly enough, as the top AMT tax rate is usually lower than the top regular tax rate of 37%), households with large families, those who are married and those with high state and local taxes. If you think you could possibly fall into this category, do your research. You can calculate your AMT yourself using Form 6251, or a tax preparation software will usually calculate it for you. If AMT does apply, I’m sorry; don’t shoot the messenger.

How to File

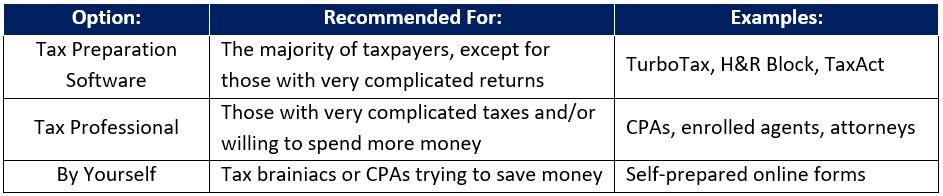

Now that you’ve learned more than you want to know about the Form 1040, how do you file the damn thing? You generally have three options:

Tax Preparation Software

This is my favorite option. Tax preparation software has come a long way and has really made tax filing almost as simple as possible. In addition, this is usually the most cost-effective option. For almost ⅓ of you, tax preparation software will come at no cost. Woohoo!! You see people stampede over one another for free food, yet few people rush to take advantage of free tax prep software. For others, the cost of the software typically depends on the complexity of your return and how many returns you file (i.e., federal, state and/or local).

If you have a relatively basic tax return, you have many cheap options. Your best option may actually come from the IRS itself. If your income is less than an established amount, the IRS provides you free software to file your return! If your income is above this amount, the IRS has no sympathy for you and instead offers free fillable forms and basic guidance. In addition, many other types of software offer free guidance for forms 1040A and 1040EZ.

If your income surpasses the IRS’ threshold for free software, you don’t qualify for the 1040A/1040EZ or you need more guidance, you’ll need to shell out some money. The most popular tax prep software is TurboTax (from Intuit), which is followed by H&R Block. Before jumping straight to a choice, take a few minutes to research your options. It’s like shopping for a pair of shoes: you want to find the best fit for the best price. These tax prep companies offer different types of software depending on the complexity of your return, so it’s your responsibility to find the software providing just enough support for your tax needs.

When considering your options, BEWARE of hidden fees: you may find a “free” software may not cover all the required schedules fitting your tax requirements (e.g., health savings account), and the starting costs can exclude state returns, which run at about $40 per state return. Think carefully before selecting your product as oftentimes you have to start from scratch if you picked the wrong service (this has happened to me, and there are few things worse in this world).

How does tax prep software typically work? As discussed above, you report your income by importing various tax forms, generally by typing in your W-2 control number and logging into your respective brokerage accounts (rarely you need to manually document your earnings). It’s that easy. For your deductions, credits, etc., the software asks you simple questions to provide you the largest tax savings. Once you calculate your tax bill (or refund) for your federal return and any applicable state or local returns, you can sign the returns and directly submit them to the respective treasury departments (simply by clicking a button in the software). The software will ask you to securely provide your banking information so that the departments can withdraw or deposit funds depending on taxes or refund owed (you also have the option to mail a check following submission).

If you end up choosing the tax preparation software route, take the time to make sure you complete all sections. You could easily miss out on thousands of dollars by skipping a deduction or credit. Like a first date with your dream crush, take it slow and show sincere attention. You’ll likely get rewarded later (wink wink).

Tax Professional

This is a nice option if you have and are willing to spend the money. Your most typical tax professionals are Certified Public Accountants (CPAs), enrolled agents and/or certain attorneys. For less-complex returns, hiring a pro usually runs you a couple hundred dollars. For more-complex returns, a pro can easily cost you several thousands of dollars. For most of you, tax preparation software will provide you more than enough guidance. If you feel that you need more guidance, consider hiring a tax professional to file one return and use that return as a basis for you to complete the return on your own the following year.

Hiring a tax professional of course takes a lot of the time and effort away from you, which can be a double-edged sword. Sure you don’t have to worry as much about the filing part, but you miss out on the opportunity to learn about those tax areas that could provide you significant savings in the subsequent year. If you do hire a tax professional, stay actively involved. Clearly you need to review and sign your return, but you should strive to remain aware of the tax rules to save you big bucks going forward.

File By Yourself

Your last option, to file by yourself, is best if you are a tax professional or confident in your tax knowledge. The IRS provides fillable pdf forms and schedules for you to complete on your own, but it’s your responsibility to make sure you accurately complete the forms to legally lower your tax bill. This puts more pressure on you as you don’t have a software or pro as a backstop, but this method can save you money if you have the tax knowledge to do so.

Federal, State & Local

Regardless of the method you choose, do not forget about your state and local returns, and do not assume the tax rules for these returns are the same as those for your federal return. Each state and municipality has its own rules and regulations, so different states and municipalities can give you very different tax bills or refunds. Tax software will make this easy for you, but you still want to be familiar with the state and local tax rules that apply to you so that you can find ways to reduce your tax bill.

Document Retention

How long should you keep your tax documents and support filed away? I’ll fall back on an attorney’s favorite answer: it depends. The IRS details specific record retention rules on its website, but in general you should retain your tax documentation for at least 3 years. Other scenarios, such as for not filing a return, unreported income or filing a fraudulent return, can require you to retain your tax documentation for several more years or even indefinitely.

Time to Partay

Whew, that was exhausting! Hopefully you didn’t flat-line on me. If you can’t get enough of this and want to learn basic tax strategies, there’s another post just for you. Now go celebrate with a cold one and comment with any questions!

Keep them coming!

Just for you Nancy. Thanks for reading!

way too long

One of your best posts yet, Adam

Thanks again, Caitlin!

Was hesitant to read this, but so glad I did. Excellent article that I will be revisiting

Thanks for reading, James. Feel free to subscribe for more posts

thanks for making taxes a little less dull

Glad I could help

lol I like the pizza analogy

Thought it brought the point home! Don’t mess with my pizza

Another one to pass along 🙂

Thanks again, Alec!

If you are looking for a solid intro to taxes, you have found it. Good post

Thanks, Owen. Glad you like it

I don’t care what anyone says I will always love receiving a refund!!

I did my best. Enjoy it!

Thank you for being so thorough!

Thank YOU for reading!

why Pete Rose isnt in HOF

A shame for such a phenomenal player

Forwarded this directly to my 19 and 17 year-olds. They need to learn this.

Thanks for passing along!

Probably the best overview of individual taxes that I’ve seen. Does not cover a lot of the specific details but not necessary for most people.

Thanks, Paul. Glad you liked it

Well you can’t say that wasn’t thorough.

Taxes can be exhausting

no way I’m remembering this, so please keep this up

Will do

like

Thanks, Srikant

funny!

Glad you liked it!