Chances are you’ve heard that the Federal Reserve has drastically cut interest rates to counteract the impact of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. But what does this mean? And how does this impact you? Here’s what you need to know.

What is the Federal Reserve?

The Federal Reserve (the “Fed” for short) is the central bank of the United States. It’s been around since 1913, after the previous U.S. central bank shipped all its money on the Titanic. No, not really. Congress established the Fed in that year primarily to prevent financial panics. Now, the Fed has two main responsibilities as mandated by Congress: (1) maintaining price stability and (2) achieving maximum employment.

The purpose of a central bank is to provide security and stability to a nation’s monetary and financial system. In particular, central banks are responsible for managing national monetary policy, supervising and regulating depository institutions, maximizing employment and handling the nation’s finances (e.g., making payments, selling government securities and managing cash/investments). In this capacity, the Fed is the driver of the U.S. financial system: it can rev the engine or it can pump the breaks, implementing certain policies in hopes of smoothing out the ride.

Who’s in charge of the Fed? That would be a board of seven “governors” appointed by the U.S. President and confirmed by the Senate. These board members are responsible for analyzing current economic conditions, both domestically and abroad, and enacting responsive policies, ranging from controlling the amount of U.S. currency and stabilizing U.S. interest rates to enforcing regulations and reserve requirements on banking institutions.

The majority of the time you hear about the Fed in the news, it’s related to the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). This is the component of the Fed that is in charge of U.S. monetary policy and thus controlling U.S. inflation, interest rates and the strength of the U.S. dollar. The FOMC—comprising the seven members of the Board of Governors (mentioned above), the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (there are 12 total Federal Reserve Banks) and presidents of four other Reserve Banks (on a rotating basis)—usually meets eight times a year to discuss the economy and establish policies/actions to maximize employment, stabilize economic growth and stabilize prices.

Why does the Fed change interest rates?

Interest rates are one of the tools the Fed has at its disposal to manage inflation and economic growth (including employment). As we all know, interest is the cost of borrowing. If interest rates are high, the cost of borrowing is high: this leads to less borrowing, less spending, lower inflation and generally lower economic growth. The opposite is true for low interest rates: borrowing is cheaper, leading to more borrowing, more spending, higher inflation and higher economic growth. The Fed can thus lower or raise interest rates to control inflation and the economy. To put all this in context, let’s take a brief ride back in history:

On December 16, 2008, in the heart of the Great Recession, the Fed dropped its benchmark interest rate to virtually zero for the first time in history. To be more accurate, the Fed lowered its overnight federal funds rate to a target range of zero to 0.25%. The primary reason for the miniscule rates? America was in recession. The Fed didn’t touch this rate for seven years when, in December 2015, the Fed began raising interest rates at a very slow, gradual pace.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, consider paying 18% interest on your mortgage. What? No way! Way. That’s what people were doing in 1980. The late 1970’s and early 1980’s had astronomically high interest rates. The reason? Double-digit inflation. The inflation was believed to stem from an oil crisis, high government spending, currency speculation and various other hypothesized reasons. As some perspective, inflation averages around 2% per year, so yes, inflation in excess of 14% was very high. In response, Fed Chair Paul Volcker opted to raise rates to solve the hyperinflation epidemic, which eventually reached its peak in March 1980.

So you have these two extreme scenarios: one in which the Fed lowers interest rates during a recession, and one in which the Fed hikes up interest rates to combat inflation. These scenarios highlight two of the most common reasons for the Fed’s open market operations. Monetary policy is all about planning and reacting: the Fed implements its open market operations based on trends in the economy and the desired outcome.

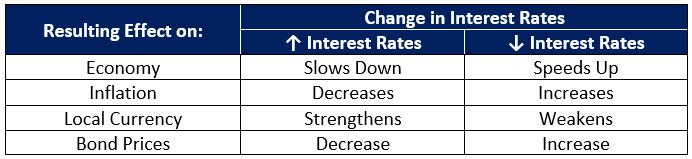

The following chart displays the general reaction of certain economic factors with interest rate fluctuations:

If you’re trying to memorize this chart, STOP. You shouldn’t try to memorize anything in this post; rather, strive to understand it. That’s how you’ll truly learn and remember the concepts when you need them.

Low Interest Rates: Think about what happens when the Fed lowers interest rates. Lower interest rates decrease the cost of borrowing and thus allow more people to borrow money. The increase in borrowed funds puts more money in consumers’ pockets, theoretically boosting consumption, the economy and inflation. The Fed thus implements this “easy money” policy when the economy is in the toilet and needs a boost.

With lower interest rates, U.S. investors search for investment opportunities with higher rates of return abroad. These foreign investments require the use of foreign currencies, leading U.S. investors to sell their U.S. dollars to acquire the related foreign currency. This decrease in demand for U.S. dollars decreases the value of the U.S. dollar compared to foreign currencies, causing the U.S. dollar to weaken.

Something very important to remember: bond prices and interest rates (i.e., yields) have an inverse relationship. If you invest in a bond earning 3% per year (coupon rate) and interest rates fall to 1%, the value of your bond increases because other investors can now only get 1% interest from an investment in a similar bond (allowing you to now sell your bond at a premium). Thus, as interest rates decrease, bond prices tend to increase.

High Interest Rates: What about when the Fed increases interest rates? You can equate an interest rate hike with pumping the breaks on the economy. Opposite of the example above, higher interest rates lead to a higher cost in borrowing, which leads to fewer people borrowing money, lower spending and less money in the market, thus scaling back on consumption, economic growth and inflation.

Consider the economic environment and rapid recovery following the Great Recession: the Fed raised interest rates consistently between 2015 and 2019. The Fed raises interest rates to reduce inflation and/or prevent the economy from overheating. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of money, and too much inflation can wreck havoc by disincentivizing saving, making basic commodities too expensive, hurting debt holders and leading the government into a downward spiral of printing more and more money (case in point is Zimbabwe’s currency leading up to 2008—go find yourself one of its 100 trillion bank notes). But what’s wrong with an overheating economy, you ask? Economies that expand too rapidly often lead to bubbles, which are bound to pop (think dot-com bubble in 2000 and housing market bubble in 2008). In addition, as we saw in 2008 to combat the financial crisis, the Fed relies on the strategy of cutting interest rates in the event of a recession. If interest rates are already rock bottom at the time of a recession, the Fed lacks a major lever to pull in this scenario.

If the Fed raises interest rates, foreign investors will invest more money in American investments (e.g., US treasuries) to take advantage of the higher interest rates (i.e., higher rates of return). To make these investments, investors will require more U.S. dollars, increasing the demand for dollars. The increase in demand increases the value of the U.S. dollar compared to other foreign currencies, causing the U.S. dollar to strengthen.

Once again, consider the inverse relationship of bond prices and interest rates. If you invest in a bond earning 3% per year (coupon rate) and interest rates climb to 5%, the value of your bond decreases since other investors can now invest in a similar bond but earn 5% (requiring you to now sell your bond at a discount). Thus, as interest rates increase, bond prices tend to decrease.

When the Fed drops interest rates, this is known as expansionary monetary policy or quantitative easing (you’ll hear the term “QE”), referring to expansion of the economy and “easy” money. When the Fed raises interest rates, this is known as contractionary policy or quantitative tightening (rarely you’ll hear “QT”), referencing the goal to contract the economy and tighten the money supply.

The rules described above are general guidelines and not always the case. For instance, bond prices usually have the expectation of interest rate fluctuations already baked into the price, so the price of a bond may not always increase (decrease) when interest rates fall (rise). In addition, sometimes the Fed may have conflicting desires related to interest rate movements. For instance, when the Fed began raising interest rates again in 2015, the Fed wanted to prevent the economy from overheating from the easy money policy over the previous seven plus years. However, inflation was still low and the U.S. dollar very strong. Even though the Fed wanted inflation to increase and not further add to the strength of the U.S. dollar, the Fed still elected to raise interest rates to counterbalance the impact of historically low interest rates since the Great Recession.

How does the Fed change interest rates?

We’ve covered the why, so let’s get to the how. When the Fed adjusts interest rates, it’s actually changing the federal funds rate, sometimes called the overnight federal funds rate. The federal funds rate is the interest rate commercial banks charge each other for short-term loans, usually overnight, on balances held at the Federal Reserve. This can get confusing, so let me paint you the picture:

To protect depositors and the general economy, the Fed requires banks to maintain a certain reserve amount on a daily basis. Banks can maintain this required reserve—known as federal funds—as cash in its own vault or as deposits with the Federal Reserve.

Based on each bank’s day-to-day operations, banks may have deposits above or below the required reserve at the end of each day. If a bank expects to have a reserve balance in excess of that required, it will lend the excess amount to banks that expect to have a shortfall in reserves at the end of the day. The interest rate these financial institutions charge each other for overnight loans to meet the Fed’s reserve requirements is the federal funds rate.

Unfortunately for the Fed, it can’t just lay the hammer and “force” banks to use a certain federal funds rate. Rather, the Fed uses open market operations, which is just a fancy term for buying and selling U.S. securities in the very banking market it regulates.

How Fed Increases Rates: If the Fed wants to raise interest rates, it sells Treasury securities (i.e., bonds) to banks in exchange for cash, thus reducing the banks’ reserves. The drop in reserves means banks need to borrow more money, allowing banks to increase the federal funds rate to match the increase in demand. On top of this, the increase in supply of Treasury securities drops the price of those securities. As we learned earlier, price and yield go in opposite directions, so yields (i.e., interest rates) on Treasuries increase as well. Higher rates everywhere!

How Fed Decreases Rates: Now for the opposite scenario. If the Fed wants to lower interest rates, it buys Treasury securities (i.e., bonds) from banks, thus increasing the banks’ reserves. Higher reserves equate to an excess of reserve funds, forcing banks to drop the federal funds rate to persuade banks to borrow the extra reserves. Furthermore, the increase in demand of Treasury securities increases the price of those securities. Higher Treasury prices result in lower Treasury yields, meaning the interest rates on Treasuries decrease as well.

In summary, the Fed buys securities from banks to lower interest rates and sells securities to banks to raise interest rates. The Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee (FOMC), discussed above, sets a target federal funds rate (or range) at eight meetings each year. When you hear in the news the Fed has raised or lowered the interest rate, that’s because the FOMC has decided to change its federal funds rate range. The Fed then implements the corresponding open market operations to adjust the federal funds rate upwards or downwards to push rates towards the new target.

Since the federal funds rate represents the interest rate banks charge for loans every night, these rates trickle down to all other interest rates in the U.S. economy. Usually a change in the federal funds rate takes at least a year to impact the general economy (although the fluctuations in bond prices can directly impact longer-term rates), but it’s important to recognize just why the federal funds rate is the most important interest rate in the U.S. (or even the world, for that matter).

When the Fed lowers the federal funds rate, any given bank’s cost of borrowing is lower, so it can lower its own wide range of interest rates. Thus, mortgage rates, prime rates (the interest rates charged to the most credible customers), savings rates, SOFR (the U.S. Secured Overnight Financing Rate, which is the benchmark interest rate banks charge each other for short-term loans), credit card rates, etc. all go down! One side point to consider: the shorter the term of the interest rate, the greater the impact of the federal funds rate. In this capacity, changes in the federal funds rate have a much higher impact on short-term interest rates, such as those for short-term Treasuries, than on long-term interest rates, such as the rate on a 30-year mortgage.

How do Fed interest rate changes impact you?

Alright, so the Fed moves interest rates to manage the economy. So what? Why should you care? (Other than wowing your date this Friday with all your knowledge, that is. Disclaimer: not likely to work).

Unless you are stranded on an island or live under a rock, which probably isn’t the case if you’re reading this post, interest rate fluctuations impact you. Interest rate fluctuations impact everyone. Changes to the federal funds rate can impact you almost directly if you have any debt, have any investments or have money in savings. Changes can also impact you indirectly if you make any purchases, have a job, receive financial support or plan to take out any type of loan in the future. If you can show me a person who doesn’t fall into any of these categories, I’ll go streaking in Times Square.

Here are some ways interest rates could impact you:

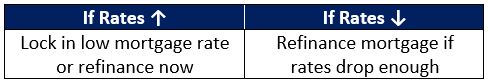

- Mortgage payments: Clearly, we all want the lowest mortgage rates on our homes we can get. If the Fed expects rates to rise, you may want to lock in a mortgage rate or refinance your mortgage as soon as possible to get a low rate. If the Fed expects rates to fall, you should strongly consider refinancing your home once rates drop enough to save you money (i.e., to offset the cost of refinancing). Finally, if you’re considering buying a home, current interest rate trends can impact your timing to jump in the market to snag a low rate on your mortgage.

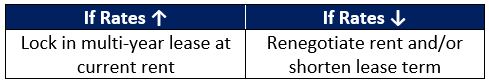

- Renting a home: Even if you don’t own or plan to own a home, your landlord is likely mortgaging your rental property. Thus, any movement in mortgage rates will likely flow through to your rental costs. If interest rates are low, see if it’s possible to lock in a multi-year lease at the current (or slightly higher) rent. If interest rates are high, it may be in your best interest to sign a shorter-term lease in case interest rates drop and rent follows suit (Note most landlords rarely reduce the rent, however, so be cautious in signing a short-term lease using this strategy). If interest rates start to drop, try to renegotiate your rent to save money on your end.

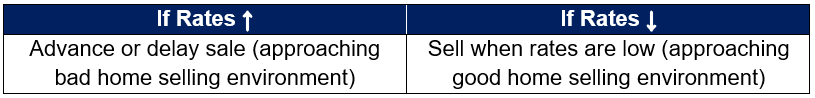

- Selling a home: If you’re on the flip side of the housing market, the challenge of selling a home aligns with mortgage rates as well. If the Fed bumps up interest rates, thus eventually increasing mortgage rates, homes will become more expensive, driving down demand for homes. This makes selling a home in a high interest environment challenging, so try to sell your home when mortgage rates are low.

- Investing in bonds: As we’ve covered, bond prices tend to move in the opposite direction of interest rates: if rates rise, bond prices generally fall, and vice versa. In this regard, if you’re looking to invest in bonds, the ideal market is when interest rates are very high (and thus bond prices are low). If you’re looking to sell bonds, the ideal market is when interest rates are very low (and thus bond prices are high).

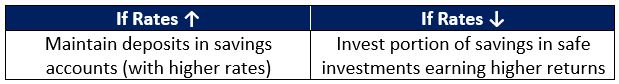

- Interest on deposits: When the Fed keeps interest rates low, the return you receive on deposits is practically nothing. If the Fed plans to raise interest rates, you’ll start to receive better returns on your savings. This incentivizes you to maintain deposits in savings, but make sure your depository institution starts to raise its rates. If it doesn’t, shop around! Also, if rates start to rise, keep the maturities of your CD and bond investments short-term, allowing you to take advantage of higher rates as rates begin to rise. If the Fed plans to drop interest rates, you may want to invest a portion of your savings in safe investment vehicles that will provide a higher return.

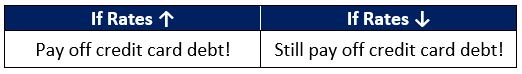

- Credit card debt: As we learned in the post Your 7 Financial Priorities, credit card debt is the Voldemort of the financial world. Avoid it at all costs. If inflation rises and interest rates follow, you’ll want to pay off this credit card debt even sooner than as soon as possible (is that possible?). Get rid of it!

At the end of the day, higher rates are good for savers and bad for borrowers. Being aware of Fed interest rate changes is half the battle. The second half is applying those changes to your current financial scenario in order to save money now and in the future.

Feel free to comment if you have any questions!

References

- https://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed.htm

really good read

Thank you!

pretty dry, but the humor helps

I’m glad you appreciate the humor

Such a good summary for my class. Thanks 🙂

Thanks again, Alex! Hope your class enjoys

Good post Adam!

Thanks again, Crystal!

Excellent. Great history lesson too

Glad you enjoyed it!

I like the Titanic comment lol

Thanks for the comment!

if rates are increasing, why is inflation increasing too?

That’s a good question, Len. At a high level, the effects of economic growth on inflation are outpacing the effects of the Fed’s interest rate hikes. Even with the increasing interest rates, consumer confidence is high, wages are increasing and the higher spending is boosting inflation, albeit slowly.

interesting. okay thank you

helpful article

Thanks for the comment, Jim