For all of you working for good ol’ Uncle Sam, whether as a civilian for the federal government or one of the many heroes serving in military, the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP) is the employer-sponsored retirement plan for you. If the TSP applies to you, this post makes saving for retirement as easy as possible.

A TSP is an employer-sponsored retirement savings plan offered to employees of the federal government, including civilian and military personnel. As discussed in the previous post on employer sponsored retirement plans, estimates indicate only about 80% of all U.S. employees have access to any company-sponsored retirement plan, and TSPs only represent a small portion of the accounts available for that lucky bunch. However, if you are one of the lucky ones to have access to a TSP, make sure you take advantage of it!

TSPs are very similar to 401(k) plans; however, TSPs in general have more standardized investment options, lower investment expense ratios and, for some, a mandatory employer match of at least 1%.

Here’s a quick history lesson to provide some context on TSPs (don’t you snooze on me):

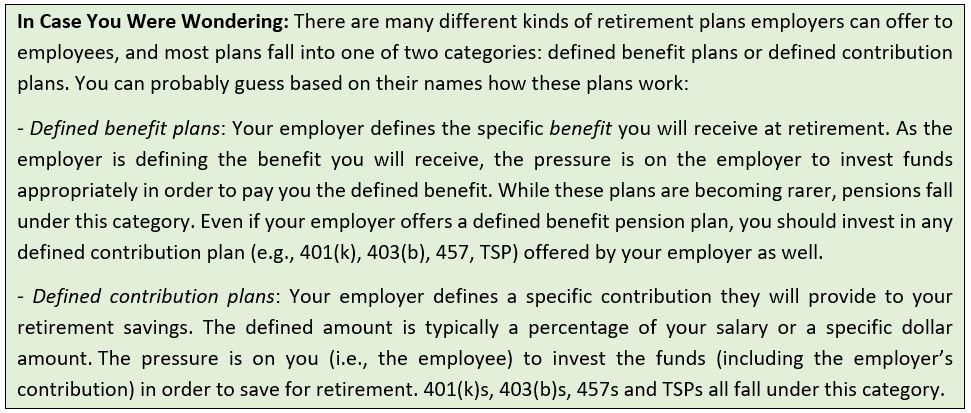

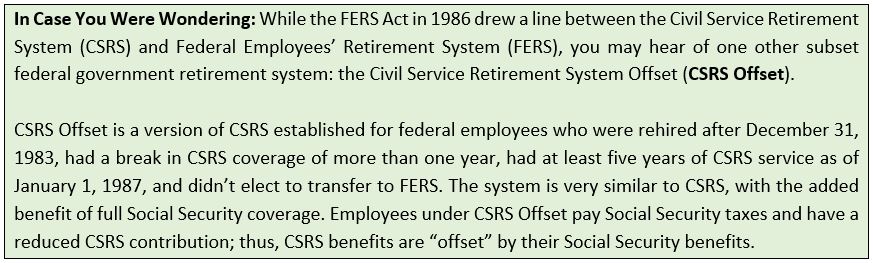

US Congress established the TSP in the Federal Employees’ Retirement System (FERS) Act of 1986. FERS is a retirement plan for federal employees that provides benefits from three different sources: (1) a Basic Benefit Plan, (2) Social Security and (3) the Thrift Savings Plan. Prior to the FERS Act, the federal government’s retirement benefit system consisted only of the Basic Benefit Plan (#1 above), a traditional defined benefit (i.e., pension) system known as the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS). Thus, the FERS act shifted the retirement benefits source from the traditional defined benefit system to a three-legged system including the defined benefit pension plan (Basic Benefit Plan), Social Security (in which federal employees did not previously participate) and a defined contribution retirement plan (the TSP).

When Congress passed the FERS Act in 1986, all federal government employees at that time had the option to convert from CSRS to FERS. Between 1986 and 2019, the federal government automatically enrolled all new employees in FERS and did not provide an option to choose CSRS. CSRS is only available to federal government employees who were in the plan before implementation of the FERS Act and chose to remain in CSRS in lieu of switching to FERS.

For the first two sources of benefits under FERS (Basic Benefit Plan and Social Security), you and your government agency fund these plans every pay period (which you will see as payroll deductions from your pay each pay period), and in return you will receive monthly annuity payments once you retire. While most American employees will receive Social Security benefits, the Basic Benefit Plan is a great perk for eligible federal government employees as more and more organizations begin to exclude defined benefit pension plans. We’ll discuss Social Security in more detail in a later post.

On November 17, 2017, President Trump signed into law the TSP Modernization Act (the Act), marking the first time the bad boy TSP has changed since its inception in 1986. True to its name, the Act is meant to modernize the Thrift Savings Plan by offering federal employees more flexibility with their retirement savings. This law, including its new withdrawal options, went into effect September 15, 2019. More on this below.

Now that you’ve received your history lesson, what in particular makes a TSP so special? Two things: (1) tax savings and (2) a potential employer match.

To start, a TSP offers tax incentives for your retirement savings. That is, you can defer paying federal and state income taxes on your retirement account savings and their investment earnings until you withdraw the money at retirement (traditional) OR you can pay federal and state income taxes up front and allow your savings and their earnings to grow tax-free, without paying taxes when you withdraw the funds at retirement (Roth). Do not underestimate the power of taxes—even 15% on such a large retirement balance is hefty, so remember that a TSP offers you CONSIDERABLE tax savings. We’ll discuss traditional vs Roth in more detail below.

Next, like puppies and carnival rides, an employer match is just plain wonderful. While all TSPs provide tax savings, TSP match percentages vary based on whether you are a CSRS employee, a uniformed service FERS employee, or a non-uniformed service FERS employee. If you are a CSRS employee, you have access to invest in a TSP to take advantage of the tax benefits of the retirement account, but you are not eligible for a TSP employer match. If you are a uniformed-service FERS employee, the secretary of your armed forces branch determines whether your TSP is eligible for an employer match. If you are a non-uniformed service FERS employee, you have very beneficial employer matching rules for your TSP. If you’re lucky enough to receive any match to your TSP, make sure you take advantage of it!

When you invest in a TSP, you control how you invest the money. The value of your account is based on the contributions made (by you and your employer) and the investments’ performance over time. Contrary to 401(k)s, which provide a comprehensive list of investment options, TSPs have one plan administrator (the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board) and offer a choice of five individual investment funds (including four index funds) as well as additional lifecycle funds (the equivalent to target-date funds). We will detail which investment options are best for you later in this post.

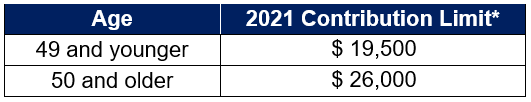

Although a TSP is a fantastic savings vehicle, it has restrictions. To prevent you from tapping your retirement account savings before retirement, the IRS imposes costly penalties for withdrawing your funds prior to retirement (with the exception of certain circumstances, which we will discuss below). In addition, each year, the IRS sets contribution limits for your retirement accounts. The IRS contribution limits for a TSP in 2021 are as follows:

*Your total contribution, including your contribution and your employer’s contribution/match, cannot exceed $58,000 or 100% of your salary ($64,500 or 100% of your salary if age 50 or older)

As shown in the chart above, employees can contribute up to $19,500 to a TSP account out of salary in 2021. Employees age 50 and over can make extra contributions of up to $6,500, bringing the total annual limit to $26,000 for those age 50 and older. Note that the $19,500 and $26,000 limits do NOT include the employer match contributions, but your total contribution (including your employee contribution and your employer’s match) cannot exceed $58,000 or 100% of your salary in 2021 ($64,500 or 100% of your salary if age 50 or older).

Before we get to the investment options that are best for you and how much you should contribute, let’s first take a look at understanding which account you should select—traditional or Roth.

Traditional vs Roth

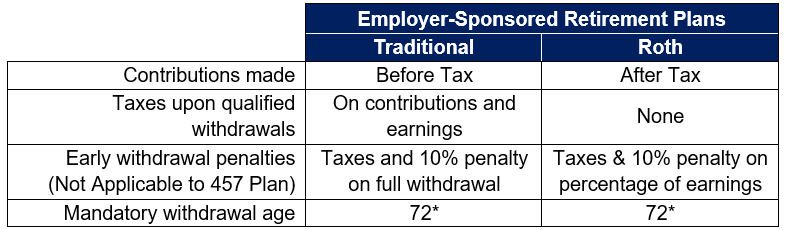

The difference between “traditional” and “Roth” plans is purely a difference in timing of when you pay state and federal income taxes (in addition to certain limitations on withdrawals). When you designate which percentage of your paycheck you want to contribute to your retirement account, your employer will deduct that amount from your paycheck to deposit into your retirement account. Whether or not those funds are taxed prior to deposit into your account or afterwards, when you eventually withdraw the funds from your retirement account, depends on whether your account is traditional or Roth.

Let’s take a look at the specific characteristics of traditional and Roth TSPs:

Traditional TSP:

- Taxes Deferred: For a traditional TSP, your employer deposits your contribution directly into your retirement account tax-free. In other words, your employer withholds no taxes on this income to pay taxes on your behalf, and eventually when you file your taxes, this contribution amount will be deducted from your total taxable income

- Taxes upon Withdrawal: Once deposited into your retirement account, your investments and their earnings (reinvested) grow tax-free until withdrawal. While you haven’t yet paid taxes on these amounts, having pre-tax investments early allows the larger amounts to compound over a long period of time. Upon withdrawal of funds from your account, you pay income taxes on both your contributions and earnings

- No Access before 59 ½: For all contributions and earnings in a traditional account, you cannot access the funds before age 59 ½ without paying taxes and a penalty (except for certain circumstances discussed below). If you withdraw funds from your account prior to this date, you will pay the applicable income taxes on the full amount withdrawn as well as a 10% penalty

- Mandatory Withdrawals at 72: Upon reaching age 72 (age 70 ½ if born prior to July 1, 1949), the IRS requires you to withdraw at least a minimum amount each year from your account and pay ordinary income taxes on the withdrawal (the government wants some money!). If you don’t take withdrawals, or you take less than required, you’ll owe a 50% penalty tax on the difference between the amount you withdrew and the amount you should have withdrawn (yikes: go remind Grandpa!)

Roth TSP:

- After-Tax Contributions: For a Roth retirement account, your employer withholds ordinary income taxes on your contribution before depositing the after-tax amount to your account. Therefore, when you file your taxes for the year, the amount contributed to your retirement account will remain in your total taxable income

- Tax-Free upon Withdrawal: Once deposited into your retirement account, your investments and their earnings (reinvested) grow tax-free. You then pay no, zilch, nada taxes on the contributions and their earnings upon withdrawal (what a deal!)

- Flexible Access before 59 ½: In order for a withdrawal from a Roth retirement account to be qualified (i.e., tax and penalty-free), you must (1) have been contributing to the account for the previous 5 years and (2) be at least 59 ½ years old. However, if you must make an unqualified withdrawal from your Roth TSP (not recommended!), such as when you make a withdrawal before the 5-year period and/or you have not yet reached the age of 59 ½, you only have to pay taxes and a penalty on the portion of the withdrawal that represents earnings (except for certain circumstances discussed below). But this does not mean you can make an early withdrawal and designate the total amount as contributions as opposed to earnings. The IRS treats each withdrawal on a pro-rata basis, allocating taxes and penalties to each withdrawal based on the total percentage of earnings in the TSP account.

To illustrate, say you have $100,000 in your Roth TSP, of which $90,000 is from contributions and $10,000 is from earnings on those contributions. Any withdrawals will be considered to come 90% from contributions and 10% from earnings, meaning 90% would be nontaxable and the other 10% would be taxable and possibly subject to a 10% penalty. To illustrate further, assume you’re 45 years old, you’ve been contributing to your TSP for at least 5 years, and you make a withdrawal of $20,000 from your Roth TSP. Of the distribution, $18,000 (20,000 x 90%) would be nontaxable and $2,000 would be taxable and potentially subject to a 10% penalty. If your tax rate is 24%, you would pay approximately $680 in unnecessary taxes and fees to make this early withdrawal. However, these taxes and fees would be significantly lower than those required for early withdrawal on a traditional TSP.

Note if you have a diversified (traditional and Roth) retirement plan account, the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board (FRTIB), the body that oversees the TSP, currently requires withdrawals to come out pro rata from both sources. However, once the TSP Modernization Act goes into effect, you will be allowed to specify how much of your withdrawal should be Roth and how much should be traditional.

- Mandatory Withdrawals at 72: Similar to the traditional account, upon reaching age 72 (age 70 ½ if born prior to July 1, 1949), the IRS requires you to withdraw at least a minimum amount each year from your account. If you don’t take withdrawals, or you take less than required, you’ll owe a 50% penalty tax on the difference between the amount you withdrew and the amount you should have withdrawn (yikes: now go remind Grandma!)

The following provides a summary of the primary traditional vs Roth TSP differences:

*Mandatory withdrawal age is 70 ½ if born prior to July 1, 1949 (changed by SECURE act beginning January 1, 2020).

TSP Exclusions to Early Withdrawal Penalties

The easiest way to avoid early withdrawal payments is to not tap your retirement account until age 59 ½ at all. Yet s**t happens, and sometimes you don’t have any other choice than to withdraw the funds early. But good news! The IRS comes to the rescue when you’re going through hardship. The IRS will not charge you the 10% penalty on non-qualified withdrawals (i.e., those traditional plan withdrawals before age 59 ½ and Roth plan withdrawals before age 59 ½ or before you’ve been contributing to the account for the previous 5 years) from your TSP under the following circumstances:

- Medical expenses (To pay for unreimbursed medical expenses in excess of 10% of Adjusted Gross Income (>7.5% if age 65 or older). We will cover AGI in our post on taxes)

- Rollovers to an IRA or other qualified plan (To transfer balance in TSP account to another qualified plan)

- Separation from company (When you retire, quit or get fired from your job during or after the year you reach age 55 [age 50 for public safety employees of certain plans]; if you do this, do not roll over your plan to an IRA or other qualified plan because this rule only applies to your current plan)

- Substantially equal periodic payments (You receive substantially equal periodic payments over your life expectancy; must be separated from employer)

- IRS Levy (IRS takes money directly from your account to pay taxes owed)

- Court-ordered domestic payments (E.g., to pay spousal payments)

- Disability (Total and permanent disability of the participant or owner)

- Death (Of the participant or owner)

It’s important to distinguish between TSPs and IRAs for early withdrawals: the IRS provides exceptions to the early withdrawal penalties for Education (qualified higher education expenses), First-Time Homebuyers (only up to $10,000) and Medical Insurance Premiums (only if unemployed) for IRA’s only; therefore, you will be penalized for unqualified withdrawals from your TSP for these expenses.

But that’s not all! TSPs are unique in that they provide even more exceptions to the early-withdrawal penalty. In particular, you have three ways to withdraw money from a TSP: (1) a loan, (2) an in-service withdrawal and (3) a post-separation withdrawal.

Loans are available only to participants who are actively employed, who are in pay status, and who have contributed their own money to the TSP. In return for the loan, you’ll pay both an administrative fee (paid as a deduction from your loan proceeds) and interest on the loan (which goes back into your TSP account). Avoid taking loans on your TSP as you reduce the earnings potential of the money now excluded from your tax-advantaged account. In addition, if you default on your loan, you could potentially be required to pay taxes on qualified Roth earnings, which otherwise would be tax-free at retirement.

In-service withdrawals are available to all active TSP participants. There are two types of in-service withdrawals: (1) financial hardship withdrawals and (2) age-based withdrawals. If you take a financial hardship withdrawal, you may be subject to a 10% early withdrawal penalty (on top of the federal taxes) and cannot contribute to the TSP for 6 months following your withdrawal (ouch!). If you want to make an age-based withdrawal, you can only do so if you have reached the age of 59 ½. On these withdrawals, you must pay federal, and in some cases state, income taxes on the taxable portion of the withdrawal (and the 10% early withdrawal penalty tax, if applicable).

There are various options for post-separation withdrawals. In general, if you leave federal government service during or after the year you reach age 55 (or the year you reach age 50 if you are a public safety employee), the 10% penalty tax does not apply to any withdrawal you make that year or later. Upon reaching age 72 (age 70 ½ if born prior to July 1, 1949), the IRS requires you to withdraw at least a minimum amount each year from your account and pay ordinary income taxes on the portion of your withdrawal that comes out of your traditional balance.

Which One to Choose – Traditional or Roth?

There’s an ongoing debate and many example calculations about which is better: traditional or Roth. If you’re a member of the U.S. Armed Forces who serves in a combat zone (in accordance with the Armed Forces definition), then the answer is easy: Roth! Why? If you’re a member of the U.S. Armed Forces who serves in a combat zone, you can exclude all or a portion of your income from taxes. If you elect to contribute to a traditional TSP, earnings on your tax-exempt contributions will be taxed at withdrawal. On the other hand, if you elect to contribute to a Roth TSP, income earned in a combat zone is effectively excluded from income taxes: the income is tax-exempt, and earnings will be tax-free at withdrawal. Therefore, if you are a member of the military in a combat zone and thus eligible for tax-exempt income, contribute to a Roth TSP so that you will not owe taxes on any earnings at withdrawal.

For everyone else, most people will tell you a Roth retirement account is the better option, if available. But this is not necessarily true. Your choice should really depend on your circumstances and, specifically, how much higher (or lower) you think your tax rate will be during retirement.

Those in favor of the Roth account claim the small tax bill upfront—in exchange for what would otherwise be an undoubtedly larger tax bill later—provides more tax savings and prevents you the burden of, and uncertainty in, paying taxes at retirement. On the other hand, those in favor of the traditional account claim these plans allow you to invest more now (assuming you haven’t reached the annual limit) from pre-tax dollars which will experience compound growth and in many cases create a higher after-tax return than a Roth account. Decisively determining which plan is best for you requires a detailed calculation with many assumptions regarding your income and tax rate at retirement. I don’t know about you, but (a) I don’t have a clue what my retirement income will be like yet and (b) I don’t really feel like paying a financial adviser to guess my future situation either.

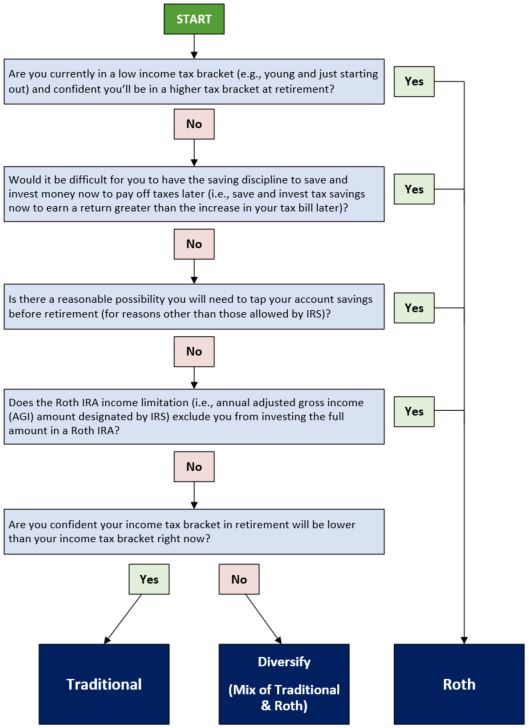

The diagram below simplifies the traditional vs Roth TSP decision for you (note there is a different decision tree for traditional vs Roth IRA). This decision matrix is not perfect, but it will give you a good reference point on which you can base your decision.

As shown above, if you don’t confidently know whether your income tax rate will be higher or lower in retirement than it is today, it would be wise to hedge your bets and split your contributions between a traditional and Roth TSP. Keep in mind, however, you’ll still be capped at $19,500 (or $26,000 if you’re age 50+) for your total annual contributions (e.g., $9,750 to traditional and $9,750 to Roth).

Employer Match

Other than tax savings, the other huge potential benefit of a TSP is the employer match. This is free money, people! Employers can offer to match your TSP contributions up to a percentage of your salary as a way of encouraging you to contribute to your plan. In particular, an employer match is part of a company’s benefits package to you; so when you’re job hunting, it’s worth considering the percentage at which prospective employers match retirement account contributions.

One of the biggest mistakes you can make, especially for those of you just starting your careers, is not contributing the maximum percentage of your salary at which your employer will match. What does this mean? Frequent employer match terms are as follows: the employer matches 50% of employee contributions on the first 4% of salary the employee contributes. In this situation, you would want your contribution percentage to be at least 4%.

To illustrate, assume Johnny works for a company offering the matching terms stated above (match of 50% on first 4% of salary the employee contributes). His salary is $50,000, and he has elected to contribute 10% of his salary to a traditional TSP. Each year, Johnny would contribute $5,000 (10% of his salary) to his TSP. In addition, each year, Johnny’s company would contribute $1,000 (50% x 4% x $50,000) to his TSP. The total yearly contribution made to Johnny’s TSP would be $6,000. Note even though Johnny contributed 10% of his salary, the company only matches 50% up to 4% of his salary.

Assume the same circumstances for Johnny except now he decides to contribute only 2% of his salary to his TSP. Johnny would contribute $1,000 (2% of his salary), and his company would contribute $500 (50% x 2% x $50,000). Johnny missed out on $500 in free money by not contributing another 2% of his salary! Boooo Johnny! To sum up, the minimum Johnny should contribute to his TSP is 4% of his salary.

Employer match rules for TSPs are complicated, so strap yourself in:

For TSPs, your employer match depends on whether you are a CSRS employee, a uniformed service FERS employee or a non-uniformed service FERS employee. If you are a CSRS employee, you have access to invest in a TSP to take advantage of the tax benefits of the retirement account, but you are not eligible for a TSP employer match (sad day). If you are a non-uniformed service FERS employee, you have very beneficial employer matching rules for your TSP, as discussed below. If you are a uniformed-service FERS employee, your employer match rules and retirement plan options depend on when you joined the military (more on this below).

If you are a non-military FERS employee, whether you contribute to your TSP or not, your agency automatically contributes 1% of your income as an employer match to your TSP. For example, if you make $50,000 per year, your agency will automatically contribute $500 to your TSP each year. Not a bad deal!

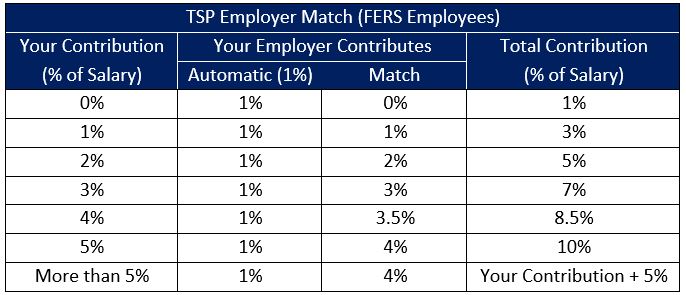

In addition to these automatic contributions, if you are a non-military FERS employee, you are also eligible for an employer match based on the amount you contribute. Specifically, your agency will match the first 3% of your salary on a dollar for dollar basis and the next 2% of your salary 50 cents per dollar you contribute. After 5% of your salary, your agency will not match your additional contributions. The following table illustrates these employer matches:

If you are a military FERS employee, the 2016 Defense Authorization Act changed your retirement plan and employer match options beginning in 2018 (known as the “Blended Retirement System” or BRS). Prior to this law, the secretary of your armed forces branch determined whether your TSP was eligible for an employer match. Now, each new military FERS employee enrolls in a retirement plan consisting of a reduced pension (eligible after 20 years of service), an automatic 1% employer match to his/her TSP (after 60 days of service), up to an additional 4% match if the employee contributes 5% of his/her salary (eligible at beginning of third year of service), an option for continuation pay (after 12 years of service) and a partial lump-sum option in exchange for a smaller pension. Even certain military personnel enrolled in TSPs prior to 2018 have access to this new retirement plan. The changes are as follows:

- If you joined the military before 2006, your current retirement plan will not change.

- If you join the military in 2018 or later, you will automatically enroll in the new plan.

- If you joined the military between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2007, you have a choice to remain in the current plan or join the new plan.

If you joined the military between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2017, make sure you crunch the numbers to determine whether the match, offset by a reduced pension, makes financial sense. Oftentimes organizations create new plans to reduce expense, so be careful before deciding to switch to the new plan. For those who join the military in 2018 or later, you will automatically enroll in the TSP match with a reduced pension.

For those sticking with the old, pre-2018 TSP, as a general rule of thumb, uniformed services members do not receive employer matching contributions (personally, I’m glad to see this is changing). If you are a uniformed service member, your income can consist of basic pay, incentive pay, special pay or even bonus pay. You may elect to contribute any percentage (0% to 100%) of your basic pay, up to the annual IRS limit ($19,500 in 2021) to your TSP. If you contribute at least 1% of your basic pay to your TSP, you can also contribute any percentage (0% to 100%) of your incentive pay, special pay or bonus pay up to the annual IRS limit. Per TSP rules, the secretary responsible for each service may designate critical specialties for matching contributions. Members serving in those specialties who agree to serve on active duty for 6 years may be eligible for matching contributions during the 6-year active duty obligation. If these circumstances apply to you, you should inquire of your TSP administrator to determine the percentage you should contribute to obtain the maximum employer match.

Finally, remember you don’t automatically vest in your employer contributions to your TSP. In general, you vest in these employer matches once you have worked for the government for three years. However, as these vesting rules vary, you will want to research your TSP’s vesting rules, especially if you’re considering leaving your agency. You should be able to determine the vesting period, if applicable, by reading your plan’s terms or contacting your agency’s HR department.

How Much to Contribute

Just like other employer-sponsored retirement plans, you want to contribute at least the percentage which will provide you the maximum employer match.

If you are a FERS employee and were hired after July 31, 2010, your agency automatically deducts 3% of your basic pay from your paycheck each pay period to deposit into your TSP account—that is, unless you have made an election to change or stop your contributions.

For non-military FERS employees, and military FERS employees who have opted into the new retirement plan, you will want to contribute at least 5% of your salary to your TSP in order to receive the full 5% employer match (refer to the table above). For military FERS employees under the old, pre-2018 TSP, you will need to determine whether an employer match is applicable to you; if so, make sure you contribute enough to receive the maximum amount of free money.

If your agency does not provide an employer match, you should still prioritize contributing as much as possible to your TSP and IRA (after establishing your immediate obligation and emergency funds and paying off all high-interest-rate debt). Due to the low fees offered for TSP investments, it may be in your best interest to max out your TSP to the IRS limit before contributing to your IRA. However, you will need to compare the fees for your particular investment choices.

With the above guidance in mind, most experts recommend 10% of your salary as a good starting point, but even many frugal, savvy, young professionals contribute 25% to even 30% of their salaries. These percentages should not be your reference point, however; first get through your first four priorities (immediate obligation fund, emergency fund, maximizing employer match and paying off high-interest debt) and determine how much money remains. As all contributions must originate as deductions from your paychecks, you won’t be able to deposit this amount directly into your retirement account. Rather, you’ll need to set a contribution percentage (this requires some math and guessing on your part) for your employer to deposit the designated percentage of your paycheck directly into your TSP account. Note this contribution and the percentage you choose will be recurring for every paycheck (until changed), but you can change the contribution percentage as often as you would like.

Determining the right contribution percentage can involve some trial and error. Thus, you should adjust your contribution percentage as often as necessary to get a sense of the appropriate percentage for you, especially if you start with a percentage much higher than you will be able to sustain. Remember, however, to not be overly conservative on your contribution percentage: if you have extra cash sitting in your checking or savings accounts (unrelated to your immediate obligation and emergency funds), that money could be sitting in your retirement account reaping the wonderful tax and match benefits (assuming you haven’t already surpassed the contribution limit).

Whatever that amount is, once again, at the very least you should invest enough to receive the full match offered by your agency. This is the freest (yes, that’s a word) money you will ever receive, so do not forget this very important advice.

TSP Contribution Limits

As mentioned above, federal government employees can contribute up to $19,500 to a TSP account out of salary in 2021. Employees age 50 and over can also make catch-up contributions of $6,500 in 2021, bringing the total annual limit to $26,000 for those age 50 and older. The maximum total contribution, including employee and agency contributions, in 2021 is $58,000 or 100% of your salary ($64,500 or 100% of your salary if age 50 or older).

However, if you are a uniformed service member in a designated combat zone and thus receiving tax-exempt pay, the IRS annual employee contribution limits do not apply to you! Therefore, you can contribute up to the total annual limit of $58,000 (remember, to a Roth TSP!), which is a huge tax benefit you should not let slide. One caveat for these personnel: only Roth catch-up contributions are allowed from tax-exempt pay (which works out well since combat zone military personnel should only be contributing to a Roth TSP anyways!).

Which Investment(s) Should I Choose?

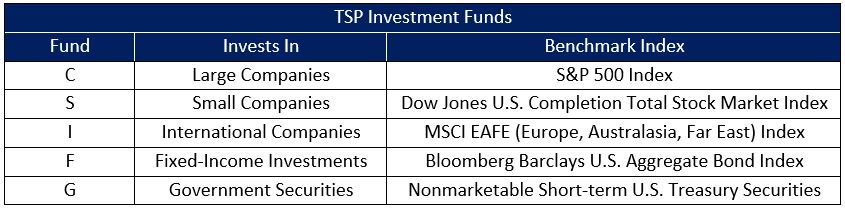

The TSP has one plan administrator: the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board. Rather than offering a wide portfolio of well-known mutual funds, annuities or individual securities, the TSP offers a choice of five individual investment funds (including four index funds) as well as additional lifecycle funds (the equivalent to target-date funds). The five investment funds include the following:

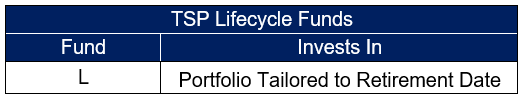

You can also opt to invest your TSP in lifecycle (L) funds which, similar to target-date funds, strive for higher risk/return early in the investment cycle and gradually become more conservative as you reach your anticipated retirement date. These L Funds are invested in the five individual TSP funds above based on professionally determined asset allocations.

You can split up your TSP savings into the investment options above however you would like. Therefore, you can create whatever portfolio best suits your investment strategy using the various funds above. However, if you’re searching for simplicity for a low cost, the L funds tailored to your anticipated retirement date are the perfect choice.

Now for the best part of TSP investments – they usually have very low fees! By collecting forfeited employer contributions from those who leave the TSP, the government covers some of the plan expense (gee thanks!). This keeps the TSP investment expense ratios very low, allowing you to often find investments with expense ratios less than 0.03%. Based on the lessons we learned in our earlier post about compound interest, the savings on these lower expense ratios can be significant over the long-term.

Setting up your TSP

If you are a FERS employee, your agency will automatically enroll you in a TSP. If you are a CSRS employee, your agency will establish your account after you make a contribution election using your agency’s automated system (assuming it has one).

Upon starting your position, your agency should provide you a summary description of the TSP and instructions for making an election to start, change or stop your TSP contributions. Depending on your agency, you will be instructed to use your agency’s electronic system or submit various TSP forms. Once you create and log in to your account, you will be able to select your TSP contribution percentage and the investments in which you will invest. Upon finalizing your contribution percentage and investments, your agency will automatically deduct the funds from your paycheck to invest in the TSP on your behalf. You can monitor your TSP balance by logging into your account via the administrator’s website. If you have questions about your TSP balance or investments, contact your agency representative or TSP administrator.

TSP Modernization Act

On November 17, 2017, President Trump signed into law the TSP Modernization Act (the Act), marking the first time the TSP has changed since its inception in 1986. True to its name, the Act is meant to modernize the Thrift Savings Plan by offering federal employees more flexibility with their retirement savings.

What’s changing?

Federal employees and retirees will have more options to withdraw funds from their TSPs. Here’s specifically what’s changing:

Lump-sum withdrawals

Currently, TSP participants may only elect one partial age-based withdrawal after they turn 59½ or one partial post-separation withdrawal after leaving the federal government (i.e., only one lump-sum withdrawal during the participant’s life). The new law removes these limits by allowing unlimited age-based and post-separation withdrawals. Thus, federal employees over age 59½ who are still working can elect multiple age-based withdrawals, and employees who have separated from federal employment can make multiple partial post-separation withdrawals.

The Act will also allow participants to take partial post-separation withdrawals if they’ve already taken an age-based in-service withdrawal, which is not currently allowed. Though it will have no impact on required minimum distributions, the new rules will permit separated participants who are over age 70½ to remain in the TSP, removing the requirement to make a withdrawal election on an entire TSP account balance.

Monthly payments

Currently, TSP participants receiving identical monthly payments can change the amount of payments only once per year (between October 1st and December 15th). In addition, if monthly payments are stopped completely, the TSP account must be closed. But not anymore! Those receiving monthly payments will be able to change the amount and/or frequency of their annuity at any time, instead of only once per year.

Withdrawal allocation

According to an official Q&A published by the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board (FRTIB), the body that oversees the TSP, the FRTIB is “adding the ability to specify how much of your withdrawal should be Roth and how much should be traditional; withdrawals currently come out pro rata from both sources.” With the ability to strategically assign the withdrawal to either their Roth or traditional account, federal employees and retirees can potentially save lots of mullah in taxes owed on those withdrawals.

Why the changes?

Congress is hopeful that this new law will drive more federal employees to keep their assets in their TSP accounts. With some of the lowest fees of all investments and oversight by the Treasury, the TSP should be as popular as the prom queen, right? Wrongo. More than half of TSP participants move the majority of their balances to other accounts once they separate from the government. By ridding the plan of its many restrictions on account withdrawals, Capitol Hill is trying to tackle this conundrum head on.

When will the changes become effective?

The bill specifically directs the FRTIB to prescribe such regulations as necessary to carry out the new changes no later than two years from the date of enactment (which would put us at November 17, 2019). Nothing changes until new regulations are put in place, so until then you are limited to the current withdrawal options.

If you have a TSP account balance when the new rules go into effect, even if you’ve begun receiving monthly payments or have taken a partial withdrawal before then, you will be able to take advantage of the new withdrawal options. However, remember that, as is currently the case, if you are receiving monthly payments and elect to make a change that affects the duration of your payments, there may be tax consequences.

For any other TSP questions, feel free to leave a comment!

References

- www.tsp.gov

- https://www.usaa.com/inet/wc/advice_deployment_menu?wa_ref=pri_global_lifeevents_deploy&akredirect=true

- https://www.tsp.gov/PDF/formspubs/tsp-536.pdf

- https://www.military.com/paycheck-chronicles/2016/03/15/10128

Helps tie together everything on the TSP website. thanks

Thanks again, Ted

USA USA USA

Thankful for our troops!

Good recommendation about Roth for military in a combat zone

Thanks for the comment, Jeff. Hope you enjoyed

that’s a lot to know

Consider it more of a reference of the most important TSP knowledge. No need to memorize all of this

Your summary of the new law is the best part. Helpful!

Thanks, Lydia. Appreciate the comment!

It’s complicated

Your relationship status or this post? Only kidding. It’s tricky with CSRS vs FERS employees, but focus on the content that applies to you. Most importantly, if you have a TSP, make sure you contribute enough to get the maximum employer match.

Where does the BRS plan fit into this article?

Thanks for the comment, Amy.

“BRS” stands for Blended Retirement System. This is actually the fancy name of the new retirement plan mentioned in the post. This new retirement system consists of a reduced pension (eligible after 20 years of service), an automatic 1% employer match to his/her TSP (after 60 days of service), up to an additional 4% match if the employee contributes 5% of his/her salary (eligible at beginning of third year of service), an option for continuation pay (after 12 years of service) and a partial lump-sum option in exchange for a smaller pension. Those joining the uniformed services on Jan 1, 2018, or later are automatically enrolled in BRS, and those members with fewer than 12 years of service as of December 31, 2017, may opt into BRS.

Ahh thanks!!