After that mess of a 2020 general election, you may want a breather from any sort of US election. Nevertheless, are you aware of the next key elections, even before the next general election in 2024? What about differences between primaries and caucuses, voting differences by state, and the purpose of the Electoral College? If you’re uneasy about any of these topics, this post has you covered.

Election Background

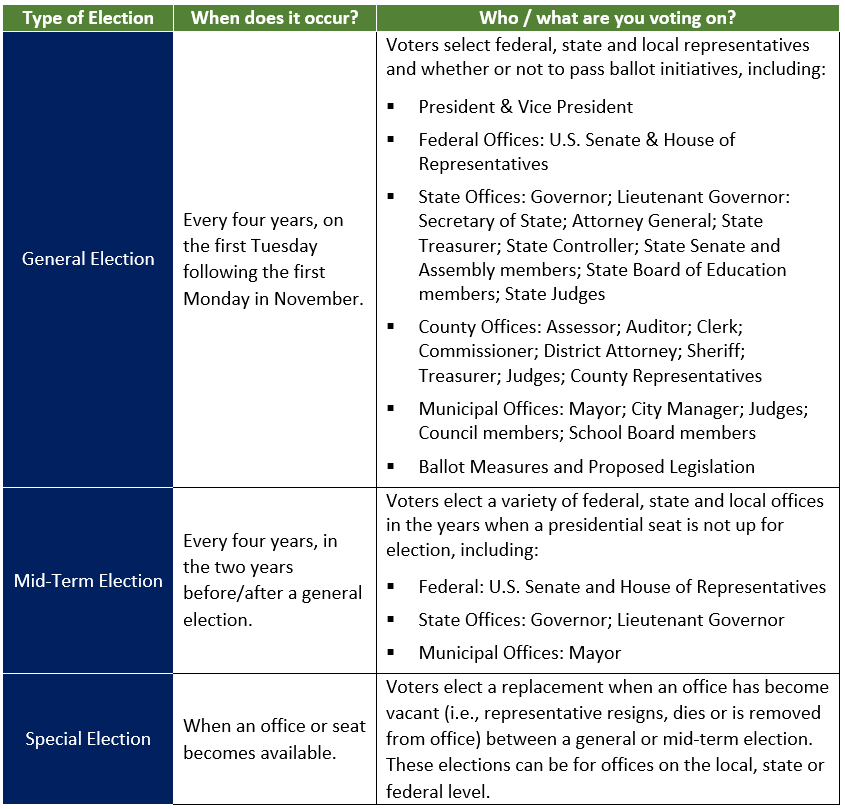

In the great US of A, there are several elections:

Accredited Schools Online

This post focuses on the general election, which takes place every four years on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. This shouldn’t take away from the importance of mid-term or special elections, however—the offices at stake in these elections can oftentimes pivot political control enough to make a significant impact to local, state and/or federal laws.

Leading up to a general election, the Presidential election attracts almost all of the media attention. And for good reason: the U.S. President, beyond serving as the U.S. head of state and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, has the power to appoint the leaders of numerous federal offices, sign legislation into law or veto bills enacted by Congress, sign treaties, issue executive orders and extend pardons and clemencies, among many other powers.

Nevertheless, the general election is about MUCH more than the president and vice president. In particular, the results of Congressional elections—including those for the Senate and House of Representatives—can be crucial. Since bills must pass both houses of Congress before going to the president for consideration, political party control of all three powers—the president, Senate and House of Representatives—can set the stage for significant legislative change in favor of one political party. This is what happened from 2009 to 2011 for President Obama and 2017 to 2019 for President Trump, years when we saw control—and an abundance of U.S. legislation and policy changes—from Democrats and Republicans, respectively. This is also the current state for President Biden: Democrats control both the Senate and the House, opening the door for significant Democrat-led legislation in the coming years.

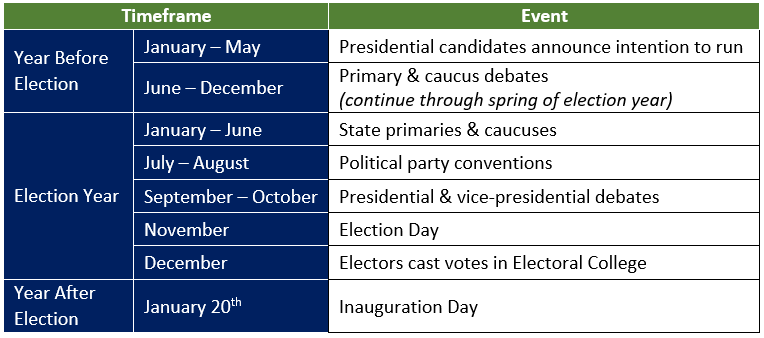

Typical Election Timeline

Before we get to the details, here’s the general timeline of general elections:

Pre-Election Process

Spring of Year Before Election

Presidential candidates announce intention to run

Presidential hopefuls generally announce their candidacy for president a year and a half before the general election. Thus, although presidential candidates may establish the groundwork several years in advance, formal presidential campaigns typically begin in the spring of the year before the presidential election.

Summer of Year Before Election → Summer of Election Year

Primary & caucus debates occur

Before political party nominees square off in the general election, candidates compete for their party’s nomination in caucuses and primaries across the country. In the United States, the majority of candidates belong to one of two major parties—the Republican Party or the Democratic Party. Each party selects its presidential candidate in the months leading up to the November general election using selection methods known as primaries and caucuses (more on this below).

Debates for these primaries and caucuses begin the summer before an election year and typically recur over the next eight months, preceding the caucuses and primary elections which occur January through June of the election year.

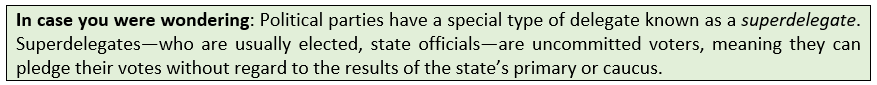

An important point here: you may hear the term “delegates” in relation to primaries and caucuses. At a high level, delegates include a group of volunteers, local party chairs or others that are heavily involved in the state’s politics. Delegates are ultimately responsible for choosing the party’s nominee at the national convention. In order for a candidate to receive the party nomination, he or she must win a majority of the party’s delegates. Delegate allocation in primaries and caucuses varies by state: some states allocate delegates based on proportion of votes, whereas other states allocate delegates based on a winner-take-all approach. When a candidate wins delegates in a state, those delegates are presumed to vote for the candidate at the convention. Each political party has a specific number of delegates, and a candidate must accrue a majority of the delegates to secure the party’s presidential nomination.

Primaries vs Caucuses

The U.S. Constitution does not mandate how political parties select their presidential nominees. With this in mind, political parties and states set the rules and guidelines, resulting in a unique primary or caucus for each state. While similar, there are key differences between these two selection methods:

- Primary: Primary elections are pretty straightforward. Similar to the process for the general election, voters show up to their assigned polling location and cast a secret ballot for the candidate of their choosing. But not all primaries are the same: some are “open” primaries, meaning voters can vote for a candidate from any party, whereas others are “closed” elections, in which voters can only cast a ballot in the primary of the party for which they’re registered. Depending on the state’s rules, delegates are allocated in proportion to the percentage of votes received by each candidate (proportional primary) or distributed in total to the candidate who receives the most votes (winner-take-all primary). Primaries are run by state governments, so political parties have very little flexibility in setting their own rules.

- Caucus: Caucuses, on the other hand, are far from straightforward. Voters do not simply show up to their polling place, cast their ballot and leave with an “I Voted” sticker. Rather, a caucus is considered to be a “meeting of neighbors.” Voters in each local precinct gather at a local venue to discuss the election, give fervent speeches on behalf of candidates, debate issues and, ultimately, conclude on a presidential nominee. Unlike primaries, caucuses are held at a specific time of the day, and votes can be tallied in a variety of ways—such as casting ballots, a show of hands or dividing into groups.

To complicate matters further, local caucus results don’t directly correlate to the proportion of delegates sent by each party to the national convention (although most caucuses have a certain percentage threshold to earn any delegates). And because caucuses are run by political parties (not state governments), caucus rules governing the voting procedures and distribution of delegates can vary by political party. Yes, this can get confusing.

Interestingly enough, the caucus process today is much the same as it was when political parties began nominating their presidential candidates in the 1800s. Partially for this reason, most states opt for primaries today, with only five states—Iowa, Kentucky, Nevada, North Dakota and Wyoming—still stuck in the Stone Age and relying solely on caucuses.

All presidential primaries and caucuses are typically held from January through June of the election year, with a few potentially extending into July and August. Since 1972, Iowa has always best first to host. Because it’s first, the Iowa caucus—held in January or February of the election year—is considered a pivotal proving ground for most candidates. After Iowa, each state hosts its primary or caucus races in the next several months. For the presidential election, the results of those primaries and caucuses will determine how many delegates get allocated to each candidate. Those delegates will then vote for the respective presidential candidates at the party convention, where the party will officially name the presidential nominee.

July – August of Election Year

Political parties host national conventions

After the primaries and caucuses, most political parties host national conventions. During these conventions, delegates cast their votes and the parties officially announce their presidential and vice presidential nominees.

As mentioned above, a candidate must win a majority of the party’s delegates to secure the nomination. If no candidate has achieved a majority of the delegate vote, it can get very interesting. In these instances, candidates usually pursue each other’s delegates, hoping to garner enough support to win the majority—this may occur even before the national convention itself. If there’s still no majority at the national convention, you’ll see additional delegate vote trading and rounds of voting (what’s known as a brokered or contested convention). In addition, superdelegates will participate if no candidate wins the majority after the first round of voting.

September – October of Election Year

Presidential & vice-presidential debates

This is when it really gets fun. The Presidential debates are meant to educate the American public on the most important issues facing the country and how each candidate would approach them. While that purpose is oftentimes met, these debates can provide great entertainment, showing how well each candidate handles the spotlight and can quickly react with clever answers that resonate well with voters. This is especially true when someone like Donald Trump takes the stage.

Before the presidential election, there are three presidential debates and one vice-presidential debate. These debates, sponsored and run by the nonpartisan Commission on Presidential Debates, are usually held in September and October—right before the election—at different locations across the country.

Debate format can vary, but topics discussed usually include the most controversial issues at the time. These debates typically have a small audience of citizens and have been broadcast on live television since 1976 (note the first televised debate was in 1960 between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, but candidates did not debate each other face-to-face for another 16 years).

Election Day

First Tuesday following the first Monday in November

After months and months of debates, bantering and speculation, we’ve finally reached the big day. US Election Day is held on the first Tuesday following the first Monday in November, meaning the day can fall anywhere from November 2nd to 8th in an election year. This year, Election Day is November 3rd. Get ready for a day chalked full of final campaign efforts, polling, blue states, red states, Electoral College vote counts, key race alerts, state projections and, of course, drama. Here’s generally how the Tuesday in November will unfold:

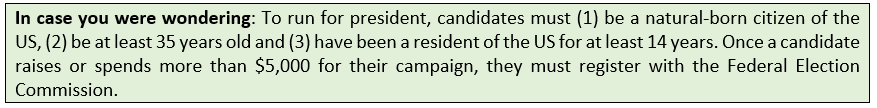

Voting Process

It all starts with the voting. To vote in US elections, you must (1) be a US citizen, (2) be 18 years old on or before Election Day, (3) meet your state’s residency requirements and (4) be registered to vote by your state’s voter registration deadline (note that North Dakota does not require voter registration). If you’re younger than 18, note that some states allow individuals who are 17 to vote in the primaries if they will be 18 at the time of the general election.

If you have not yet registered to vote, do so NOW at Vote.gov. Once you register, your state will provide you a polling location.

As with many things in the great US of A, the voting process varies by state. Because you can’t yet vote online in federal US elections, you generally have two ways to vote in general elections: going in person to a polling location or submitting an absentee ballot (i.e., mail-in voting):

- In-person polling location: You visit your assigned polling location (typically a school, community center or other public facility), stand in line to check-in with the polling workers, submit your ballot and proudly leave with your “I Voted” sticker. Most states have laws requiring some sort of identification to be shown on Election Day, so be sure to check your state’s requirements.

Voting times vary by state, but polls usually open around 6:00am or 7:00am local time and close some time from 7:00pm to 9:00pm. Most states also offer early voting, which allows registered voters to cast a ballot in person during a designated time before Election Day.

- Absentee (mail-in) voting: You fill out an application to receive a ballot, receive your ballot in the mail, complete the ballot at home and then put the prepaid envelop in the mail before the election. Every state offers absentee voting, but some states only allow you to vote absentee in limited circumstances (i.e., with a valid excuse, such as an illness, disability, travel plans or attending out-of-state school).

What’s on the Ballot?

The ballot you receive for the general election depends on your registration location. Remember, you’ll not only be voting for federal offices, but also state and local representatives, ballot measures and proposed legislation. Carefully read each proposition because your vote matters.

How a Winner is Determined

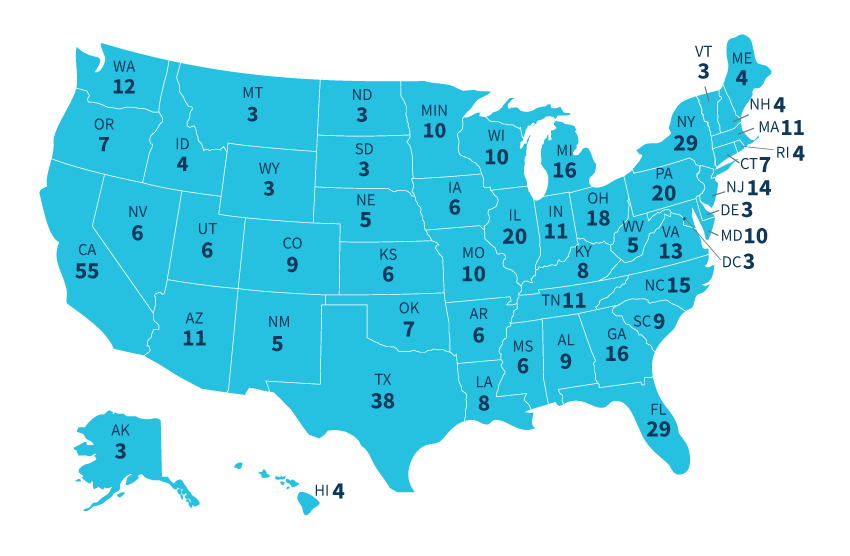

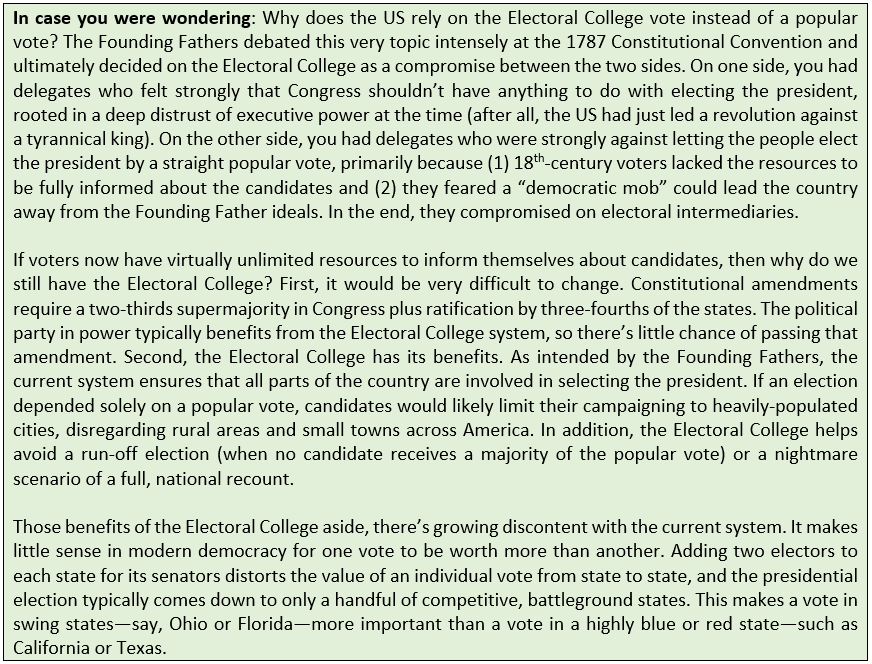

So, whichever presidential candidate gets the most votes wins, right? Wrongo. Rather than a popular vote (simply the number of votes received by each candidate), the US elects its presidents based on a state-by-state, winner-take-all system. At the center of this system is a group of officials known as the “Electoral College.” The Electoral College is a fancy name for officials, or “electors,” who vote for the president on behalf of states. A total of 538 electors make up the Electoral College, and a candidate must win a simple majority of 270 electoral votes to claim the White House.

The US allocates the electoral votes based on representation in Congress—including the sum of its senators (two per state) and representatives in the House (determined by population)—meaning more populous states have a larger number of the electoral votes. To put that into context, the six largest states by electoral vote are California (55), Texas (38), Florida (29), New York (29), Illinois (20) and Pennsylvania (20). Here’s the electoral vote allocation by state:

Image from USAGov

This is why certain states are very important to candidates, and you’ll hear the terms “red states,” “blue states,” and “swing states”:

- Red States: Historically vote Republican and are expected to do so in the election (Texas and most of the southern and mountain states)

- Blue States: Historically vote Democrat and are expected to do so in the election (California, Illinois and most of the New England region)

- Swing States: Toss-up or “battleground” states that can change depending on the candidate (Florida, Ohio, North Carolina, Arizona, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin)

Due to the winner-take-all election format, campaigns focus most of their time and money on swing states. For instance, it wouldn’t make sense for a Republican presidential candidate to campaign in California—a state that has voted Democrat at a very high rate over the past three decades—when he/she could focus that time on helping his/her case in Florida, Ohio and North Carolina, three commonly key swing states.

And based on this Electoral College system, it’s entirely possible for a candidate to become President of the United States without winning the popular vote. This is exactly what happened in 2016, when Hillary Clinton received more overall votes than Donald Trump but lost the electoral vote and election.

When will we know the results?

The first polls close at 6:00pm ET, but most TV networks begin their election coverage at 7:00pm ET. State polls then close in increments—generally moving from East coast to West coast—over the next several hours, culminating with five states that close at 11:00pm ET and Alaska that closes at 1:00am the next day. In other words, depending on how close the election is, it can be a long night. For reference, networks didn’t project Donald Trump as the winner of the 2016 election until 2:30am, when most of the East coast was snoozing. And don’t forget about results for the other federal, state and local office elections, many of which may be too close to call until well past election night.

What Happens Next?

December of Election Year

Electors cast votes in Electoral College

Although we’ll (hopefully) learn of the presidential election results on Election Night in early November, electors (of the Electoral College) don’t formally vote for president and vice president until December. At this time, the electors meet in their respective state capitals to cast their votes in accordance with the November results.

January 20th of Year After Election

Inauguration Day

The 20th Amendment to the Constitution mandates inauguration—when the president- and vice-president-elect get sworn into office, occur on January 20th (or January 21st if January 20th falls on a Sunday) of the year following election.

Various inauguration festivities occur throughout the day. After a morning worship service and procession to the US Capitol building in Washington, DC, the vice-president-elect gets sworn into office, followed by the president-elect around noon. The chief justice of the Supreme Court typically administers the presidential oath of office. After the ceremonies, the president joins a parade to the White House to begin his or her four-year term.

Then, it’s showtime to prove the voters right.

Quick Note on Voting

When it comes to voter turnout—the percentage of eligible voters who actually cast ballots—America is near the bottom. Only 55.7 percent of voting-eligible Americans voted in the 2016 presidential election, meaning almost half of US citizens just sit on their a** and hope for the best. If you’re catching a tone of frustration and disappointment, then good—that’s the point. This low of a turnout is an abomination.

For centuries, courageous people have fought for expanded suffrage. When America elected George Washington as the first US President in 1789, only six percent of the nation was allowed to vote. We’ve come a LONG way since then:

- 1856: Right to vote extended to all white men

- 1870: Right to vote extended to all men, regardless of race (yet several measures and voter intimidation still kept African Americans and other races from the polls)

- 1920: Right to vote extended to women

- 1924: Right to vote extended to Native Americans via citizenship opportunities (yet many Native Americans were still banned from the polls for decades)

- 1952: Right to vote extended to Asian Americans via citizenship opportunities

- 1965: Right to vote enhanced for people of color via the Voting Rights Act, removing discriminatory barriers that kept many people of color from voting

- 1971: Right to vote extended to those age 18 or older, reduced from 21 in light of the Vietnam War

Underlying these changes were countless individuals who fought, went to jail and even died to earn you the right to vote. This right for you to vote is the most important right granted to you as a US citizen. So, register, do your research and VOTE! The future of America depends on it.

References:

- https://www.accreditedschoolsonline.org/resources/students-and-first-time-voters/

- https://www.usa.gov/election#:~:text=A%20Presidential%20candidate%20must%20be,for%20at%20least%2014%20years

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/reference/united-states-history/difference-between-caucus-primary-election/

- https://www.cnet.com/how-to/voting-during-the-2020-election-what-you-need-to-know-about-mail-in-votes-online-ballots-polling-place/

- https://www.usa.gov/voting

- https://www.usa.gov/inauguration#:~:text=Inauguration%20Day%20occurs%20every%20four,Capitol%20building%20in%20Washington%2C%20DC.

- https://www.usnews.com/news/best-countries/articles/2018-11-02/the-us-isnt-alone-in-low-voter-turnout

- https://www.businessinsider.com/when-women-got-the-right-to-vote-american-voting-rights-timeline-2018-10#1952-the-mccarran-walter-act-grants-all-asian-americans-the-right-to-become-citizens-and-vote-10